Harvey Cox on the Age of Spirit

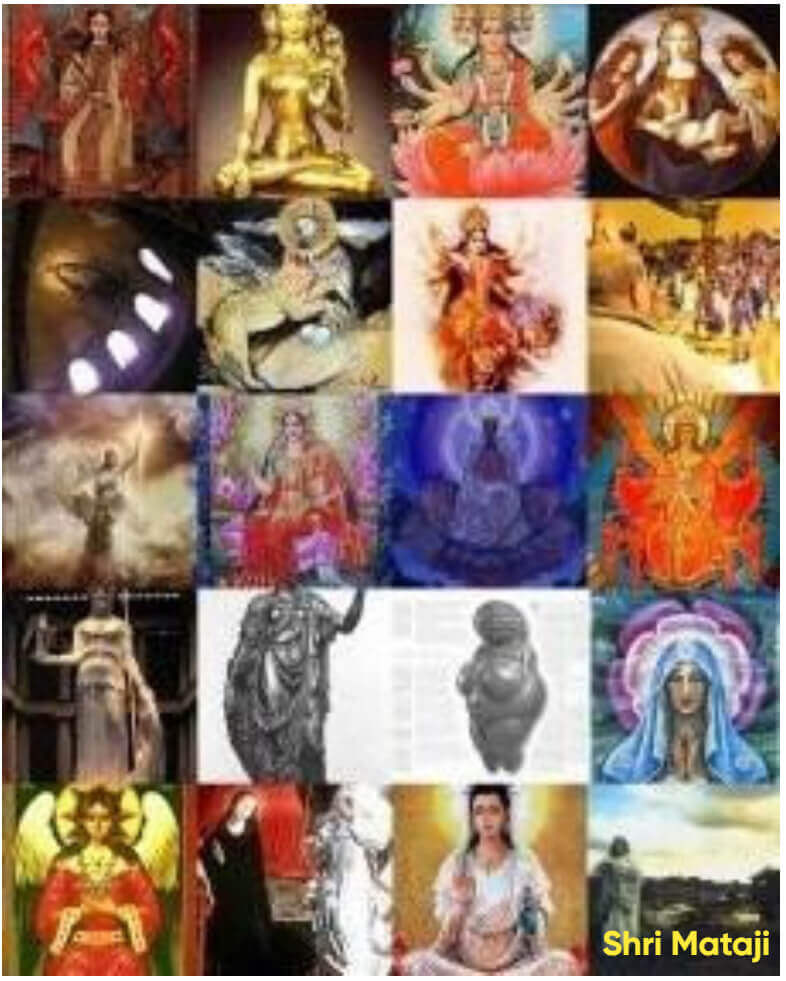

Harvey Cox’s prophetic framework divides Christian history into three phases: the Age of Faith, the Age of Belief, and the emerging Age of the Spirit. In this new age, faith is experiential, decentralized, and justice-oriented. Cox affirms that spirituality today reflects a widespread protest against institutional dogma and a return to early Christian experientialism. Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi fulfills this transition as the Paraclete promised by Jesus—guiding seekers into all truth, empowering grassroots spiritual movements, and awakening the Spirit within. The Age of the Spirit is not just coming—it has begun. The Paraclete is here. The renewal is real.

“How does the spectacular growth of megachurches like Saddleback and Willow Creek figure into this new picture? Entering Saddleback church, with its large TV screens, piped music, coffee bars, and choice of different music 'tents,' is more like strolling into a mall than stepping into a cathedral. Its architectural logic is horizontal, not vertical. The line between inside and outside is almost erased. There are now more than four hundred of these churches, with congregations of ten thousand or more. They are not fundamentalist. Their real secret is that they are honeycombs of small groups, hundreds of them, for study, prayer, and action. Sociologist Robert Wuthnow estimates that 40 percent of all adult Americans belong to one or another of a variety of small groups both in and out of churches, and that many join them because they are searching for community and are 'interested in deepening their spirituality.' He adds that these small groups are 'redefining the sacred ... by replacing explicit creeds and doctrines with implicit norms devised by the group.' Although he expresses some hesitation about this soft-peddling of theology, he nonetheless concludes that many people who grew up in a religious tradition now 'feel the need for a group with whom they can discuss their religious values. As a result ... they feel closer to God, better able to pray ... and more confident that they are acting according to spiritual principles that emphasize love, forgiveness, humility and self-acceptance.'

The recent rapid growth of charismatic congregations and the appeal of Asian spiritual practices demonstrate that, as in the past once again today, large numbers of people are drawn more to the experiential than to the doctrinal elements of religion. Once again, this often worries religious leaders who have always fretted about mysticism. Echoing age-old suspicions, for example, the Vatican has warned Catholics against the dangers of attending classes on yoga. Still, it is important to notice that virtually all current 'spiritual' movements and practices are derived, either loosely or directly, from one of the historic religious traditions. In addition, just as in the past offshoots that the church condemned were eventually welcomed back into The Mother's household, the same is happening today. In India and Japan Catholic monks sit cross-legged practicing Asian spiritual disciplines. In America, people file into church basements for tai-chi classes. Challenged by the lure of Asian practices, Benedictine monks have begun teaching lay people 'centering prayer,' a contemplative discipline that not so long ago church authorities viewed with distrust.

'Spirituality' can mean a host of things, but there are three reasons why the term is in such wide use. First, it is still a form of tacit protest. It reflects a widespread discontent with the preshrinking of 'religion,' Christianity in particular, into a package of theological propositions by the religious corporations that box and distribute such packages. Second, it represents an attempt to voice the awe and wonder before the intricacy of nature that many feel is essential to human life without stuffing them into ready-to-wear ecclesiastical patterns. Third, it recognizes the increasingly porous borders between the different traditions and, like the early Christian movement, it looks more to the future than to the past. The question remains whether emerging new forms of spirituality will develop sufficient ardor for justice and enough cohesiveness to work for it effectively. Nonetheless, the use of the term 'spirituality' constitutes a sign of the jarring transition through which we are now passing, from an expiring Age of Belief into a new but not yet fully realized Age of the Spirit.

This three-stage profile of Christianity helps us understand the often confusing religious turmoil going on around us today. It suggests that what some people dismiss as deviations or unwarranted innovations are often retrievals of elements that were once accepted features of Christianity, but were discarded somewhere along the way. It frees people who shape their faith in a wide spectrum of ways to understand themselves as authentically Christian, and it exposes fundamentalism for the distortion it is.

There is little to lament about the present decline of fundamentalism. The word itself was coined in the first decade of the twentieth century by Protestant Christians who compiled a list of theological beliefs on which there could be no compromise. Then they adamantly announced that they would defend these 'fundamentals' against new patterns that were already emerging in Christianity. The conflict often became intense. In 1922 Reverend Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878—1969) preached a famous sermon entitled 'Shall the Fundamentalists Win?' It seemed for a few decades that, indeed, they might. But now they are on the defensive. The old struggle continues, and their reduction of faith to beliefs persists. But since the emerging Age of the Spirit is more similar to the first Age of Faith than it is to the Age of Belief, the contest today goes on under different conditions. The atmosphere today is more like that of early Christianity than like what obtained during the intervening millennium and a half of the Christian empire.”

Analysis of Harvey Cox's “Age of the Spirit”

1. Cox's Three Ages of Christianity

Cox divides Christian history into three phases:

- The Age of Faith (1st–4th centuries): Characterized by experiential, communal, and Spirit-led Christianity, resembling early Jesus movements and Pauline communities. Faith was less about doctrinal assent and more about lived discipleship.

- The Age of Belief (4th–20th centuries): Marked by institutionalization, creedal dogmatism, and the rise of hierarchical authority (e.g., the Roman Church, Protestant orthodoxy). Faith became codified into rigid theological propositions.

- The Age of the Spirit (emerging now): A return to experiential, decentralized, and pluralistic spirituality, where the Holy Spirit's role is emphasized over institutional control.

Cox argues that we are currently in a turbulent transition between the "expiring Age of Belief" (where religion was reduced to dogma) and the "not yet fully realized Age of the Spirit" (where faith is dynamic, experiential, and justice-oriented).

2. The Role of “Spirituality” in This Transition

Cox acknowledges that "spirituality" is an ambiguous term, ranging from self-indulgent navel-gazing to socially engaged mystical practice. However, its widespread appeal signals a cultural shift:

- Protest Against Institutional Religion: Many people reject the "preshrinking of religion into theological propositions" by ecclesiastical authorities. Spirituality becomes a way to reclaim direct, personal encounter with the divine.

- Recovering Early Christian Experientialism: Like the first Christians, modern seekers prioritize lived experience (prayer, meditation, communal discernment) over doctrinal conformity.

- Porous Boundaries: Spirituality today borrows freely from multiple traditions (e.g., Christian contemplative prayer, Buddhist mindfulness, secular humanism), reflecting the early Christian movement's fluidity before creeds hardened.

3. The Paraclete and the Age of the Spirit

Cox's vision of the "Age of the Spirit" draws on Jesus' promise of the Paraclete (John 14:16–17, 26)—the Holy Spirit as advocate, guide, and liberating force. Key implications:

- Beyond Dogma: The Spirit "will guide you into all truth" (John 16:13), suggesting an open-ended, evolving faith rather than fixed doctrines.

- Decentralized Authority: Unlike the Age of Belief's clerical hierarchy, the Spirit empowers all believers (Acts 2:17–18), evident today in grassroots movements, megachurch small groups, and interfaith dialogue.

- Justice and Praxis: The Spirit in Scripture is linked to liberation (Luke 4:18–19). Cox worries whether modern spirituality will develop "sufficient ardor for justice," but movements like liberation theology and faith-based activism suggest potential.

4. The “Jarring Transition”

The shift from the Age of Belief to the Age of the Spirit is "jarring" because:

- Fundamentalism's Decline: Cox celebrates the weakening of fundamentalism (which reduced faith to rigid "fundamentals") but acknowledges its lingering defensive battles.

- Institutional Resistance: The Vatican's suspicion of yoga or centering prayer mirrors historical clerical anxiety over mysticism (e.g., medieval condemnations of Meister Eckhart).

- Cultural Hybridity: The blending of spiritual practices (e.g., Christian monks adopting Zen meditation) disrupts traditional boundaries, provoking both innovation and backlash.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Age of the Spirit

Cox's framework suggests that the current resurgence of spirituality—despite its ambiguities—is a sign of the Spirit breaking free from the confines of institutional dogma, much like early Christianity before it was imperialized. The “not yet fully realized” aspect implies that this age must still mature into a cohesive, justice-oriented movement, fulfilling the Paraclete's promise to renew “the face of the earth” (Psalm 104:30).

In essence, Cox sees today's spiritual seeking as a hopeful, if messy, return to Christianity's roots—a movement led by the Spirit rather than controlled by hierarchies, echoing Jesus' vision of a faith that is alive, adaptive, and transformative.

https://chat.deepseek.com/a/chat/s/a2cb73fe-918c-44b4-90de-4c341dda9228

Related Articles:

The Coming of Jesus in the Paraclete

"The theological discourse surrounding the Paraclete—the one whom Jesus promised at the Last Supper—remains one of the most profound mysteries of Christian eschatology. Many have struggled to reconcile the identity of the Paraclete with the Holy Spirit traditionally understood within Christian doctrine. However, a deeper and more precise exegesis, drawing from both scriptural sources and theological analysis, reveals that the coming of Jesus in the Paraclete signifies a distinct, divine personality arriving in the Age to Come—one who completes the mission of Christ."

The Betrayal of Shri Mataji: A Divine Tragedy

"The story of Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi and her disciples is a harrowing tale of betrayal, denial, and abandonment that echoes the tragic narrative of Jesus Christ and His closest followers. Just as Judas betrayed Jesus for thirty pieces of silver and Peter denied Him three times, Shri Mataji’s disciples—her supposed Sahaja Yogis—have committed a far greater betrayal. They have reduced her divine mission to a mere system of chakras, rituals, and mantras, obscuring her true identity as the Paraclete, the Comforter sent by God in the name of Jesus Christ."

Paraclete Papers Articles:

Part One: THE PARACLETE PAPERS: An Investigative Report on Christianity's Greatest Cover-Up

Part Two: The Paraclete's Human Personality and the Theological Fallacy of Pentecost

Part Three: The Greatest Deception in Human History: Pentecost as Satan's Trojan Horse

Part Four: Unveiling the Church Born from the Prince’s Millennia of Deception