Goddess as Brahman

Why Worshiping Devi is Direct Worship of Brahman: The Path from Illusion to Self-Realization

“Being Brahman, one who knows Brahman, attains Brahman.”

— Devi Gita 7.32

Introduction: The Profound Truth of Non-Dual Worship

In the vast expanse of spiritual understanding, few truths are as profound yet as misunderstood as the nature of Divine Mother worship in the context of ultimate reality. The passage presented reveals a fundamental insight that challenges conventional religious practice: “Many mistake worship of the Divine Mother as dualistic. However, the scriptures affirm that Lalita IS Brahman—not separate from it.” This declaration strikes at the heart of a pervasive spiritual misconception that has led countless seekers astray, binding them to external forms and rituals while the very essence of what they seek—Brahman itself—remains veiled by their own limited understanding.

The conventional approach to Devi worship, steeped in elaborate rituals, idol veneration, and dependence upon priestly intermediaries, creates what appears to be a devotional practice but in reality perpetuates the very duality that spiritual realization seeks to transcend. When devotees approach the Divine Mother as an external entity to be appeased, petitioned, or worshipped through material offerings and ceremonial procedures, they unknowingly reinforce the fundamental illusion of separation—the belief that the seeker and the sought, the worshipper and the worshipped, exist as distinct entities operating within a dualistic framework.

Yet the scriptures themselves, particularly the Devi Gita and the Lalita Sahasranama, present an entirely different paradigm. These sacred texts do not merely describe Devi as a powerful goddess worthy of devotion; they reveal Her as the very fabric of existence itself, the non-dual consciousness that appears as both the individual self and the cosmic reality. The Lalita Sahasranama explicitly states that “She is both the worshipper and the worshipped,” dissolving any notion of separation between the devotee and the divine object of devotion [1].

This profound truth carries revolutionary implications for spiritual practice. If Lalita—the Supreme Divine Mother—is indeed Brahman itself, then authentic worship cannot be a transaction between separate entities but must be a recognition of one's own essential nature. The external rituals, while potentially serving as preliminary practices for those whose minds require tangible focus, become obstacles to realization when they are mistaken for the ultimate goal. As the Devi Gita declares with uncompromising clarity: “Being Brahman, one who knows Brahman, attains Brahman” (7.32). This verse reveals that liberation (moksha) is not an acquisition of something external but the recognition of what one has always been.

The implications extend far beyond theoretical philosophy into the practical realm of spiritual liberation. The text warns that “idol worship, prayers, mantra recitations and external rituals does not remove the illusion of separation, nor do it lead to Advaita (Oneness).” This is not a dismissal of these practices as inherently wrong, but rather a recognition of their limitations. When practitioners become dependent upon external forms—whether physical idols, prescribed rituals, or priestly mediation—they inadvertently create a spiritual dependency that keeps them bound to the very duality they seek to transcend.

The path to jivanmukti—liberation while still embodied in physical form—requires a fundamental shift in understanding. Rather than seeking the Divine Mother as an external savior or cosmic force to be propitiated, the authentic seeker must recognize that the very consciousness through which they seek is itself the Divine Mother. The awareness that reads these words, the intelligence that contemplates these concepts, the being that experiences both joy and sorrow—this is Lalita herself, appearing as the individual while never ceasing to be the universal.

This document will explore these profound truths through multiple dimensions: the scriptural foundation that establishes Devi's identity with Brahman, the psychological and spiritual mechanisms by which external worship becomes a deterrent to Self-realization, and the practical path through which one can transcend ritualistic dependency to achieve direct recognition of their inherent divinity. We will examine how the very practices intended to bring one closer to the Divine can, when misunderstood, become the greatest obstacles to the realization that there was never any separation to bridge in the first place.

The journey from external worship to Self-realization is not merely an intellectual exercise but a complete transformation of identity. It requires the courage to release attachment to familiar forms and the willingness to discover that what one has been seeking through elaborate external means has been the very ground of one's own being all along. As we shall see, the Divine Mother's greatest gift is not the fulfillment of desires or the granting of boons, but the revelation that the seeker and the sought are one indivisible reality, eternally present, eternally free, eternally whole.

The Scriptural Foundation: Devi as Brahman

The Devi Gita's Declaration of Unity

The Devi Gita, embedded within the Devi-Bhagavata Purana, stands as one of the most explicit scriptural declarations of the Divine Mother's identity with ultimate reality. Unlike texts that present the divine in anthropomorphic terms or as a cosmic personality separate from the devotee, the Devi Gita reveals Devi as the very ground of existence itself. When the Divine Mother speaks in this sacred text, She does not speak as a deity addressing devotees, but as the Self addressing itself through the apparent multiplicity of individual consciousness.

The pivotal verse, “Being Brahman, one who knows Brahman, attains Brahman” (Devi Gita 7.32), encapsulates the entire philosophy of non-dual realization in a single statement [2]. This is not merely a description of a spiritual process but a revelation of the fundamental nature of reality itself. The verse operates on three interconnected levels that dissolve the conventional understanding of spiritual attainment as a linear progression from ignorance to knowledge.

“Being Brahman” (brahman san) refers to the ontological truth that consciousness—the very awareness through which all experience arises—is not a product of material processes but is itself the fundamental reality. This is not a philosophical position to be debated but a direct pointing to what is most intimate and immediate in every moment of experience. The Divine Mother, speaking as this primordial awareness, reveals that what appears as individual consciousness is actually the infinite consciousness appearing to itself as finite experience. There is no moment when one is not Brahman, no state of ignorance that actually obscures this fundamental truth, no spiritual practice that can create what is already eternally present.

“One who knows Brahman” (brahma-vid) points to the recognition of this ever-present reality. This knowing is not intellectual comprehension but direct, immediate recognition—what the tradition calls aparoksha-jnana or direct knowledge. It is the shift from experiencing oneself as a limited individual seeking connection with the divine to recognizing oneself as the very consciousness in which all experience, including the sense of individuality, appears. This recognition does not require years of practice or elaborate preparations; it can occur in any moment when the mind's habitual patterns of seeking and grasping are seen through.

“Attains Brahman” (brahmaiva bhavati) reveals that realization is not the acquisition of something new but the dropping away of what was never true. The seeker does not become Brahman through spiritual practice; rather, the illusion of being separate from Brahman dissolves, revealing what has always been the case. This is why the Devi Gita emphasizes that liberation is not a future attainment but a present recognition.

The text further elaborates this non-dual understanding when Devi declares, “My true Self is known as pure consciousness, the highest intelligence, the one supreme Brahman.” [3]. This statement reveals that when Devi speaks of “My true Self,” She is not referring to a personal identity separate from the devotee's true Self. The pure consciousness that is Her essence is the same pure consciousness that is the essence of every apparent individual.

The declaration “I alone existed in the beginning, before creation” points to the primordial nature of consciousness itself [4]. This is not a temporal statement about a cosmic history but a recognition of the timeless ground from which all temporal experience arises. Before the appearance of thoughts, emotions, sensations, and perceptions—before the entire phenomenal world—there is the pure awareness in which all experience appears.

Lalita Sahasranama's Non-Dual Vision

The Lalita Sahasranama, with its thousand names of the Divine Mother, provides a comprehensive map of non-dual realization disguised as devotional poetry. Each name is not merely a description of divine attributes but a pointer to aspects of one's own essential nature. When properly understood, the recitation of these names becomes a process of Self-recognition rather than worship of an external deity.

The most profound insight embedded in this text is the declaration that “She is both the worshipper and the worshipped” (yajamana-svarupini and pujya) [5]. This statement completely dissolves the dualistic framework that underlies conventional religious practice. In ordinary worship, there is a clear distinction between the devotee who offers prayers and the deity who receives them. This creates a transactional relationship based on the assumption of separation.

The Lalita Sahasranama reveals this entire framework as a misunderstanding of the nature of reality. When it declares that Devi is both the worshipper and the worshipped, it points to the recognition that there is only one consciousness appearing as both the seeker and the sought.

The names Chinmaya (Pure Consciousness), Brahmarupa (Form of Brahman), and Satchidananda Roopini (Existence-Consciousness-Bliss) point directly to the fundamental nature of reality [6]. These are not attributes that Devi possesses but the very essence of what She is—and therefore what every apparent individual is at their core.

Perhaps most significantly, the Lalita Sahasranama describes the Divine Mother as “the maya part of Brahman” and “the vimarsha form” [8]. This reveals that what appears as the phenomenal world—including individual consciousness—is not separate from or opposed to Brahman but is Brahman's own creative power (shakti) in manifestation. The world of experience, rather than being an obstacle to realization, is the very medium through which Brahman knows itself.

Advaita Vedanta's Harmony with Shaktism

The integration of Advaita Vedanta with Shaktism represents one of the most sophisticated developments in non-dual philosophy. While Advaita emphasizes the formless, attributeless nature of Brahman (nirguna brahman), Shaktism reveals how this same Brahman appears as the dynamic, creative principle of existence (saguna brahman). Rather than being contradictory approaches, they represent complementary perspectives on the same non-dual reality.

Adi Shankaracharya, the great systematizer of Advaita Vedanta, demonstrated this integration through his composition of hymns to the Divine Mother. This was not a departure from his non-dual philosophy but its natural expression. Shankaracharya recognized that Devi represents Shakti—the power by which Brahman appears as the world of experience. Without Shakti, Brahman would remain pure potentiality; without Brahman, Shakti would have no ground of being. They are not two separate principles but two aspects of one reality, like fire and its burning capacity.

The Advaitic principle that “Brahman is both the material and efficient cause of the universe” finds its perfect expression in Shakti philosophy [10]. Brahman as the material cause (upadana karana) means that the entire universe is made of consciousness itself—there is no matter separate from awareness. Brahman as the efficient cause (nimitta karana) means that consciousness is also the creative intelligence by which the universe appears. Shakti is the name given to this creative aspect of Brahman, the power by which the one appears as many while never ceasing to be one.

This understanding resolves the apparent paradox of how the infinite, unchanging Brahman can appear as the finite, changing world. The world is not a modification of Brahman (which would imply change in the absolute) nor is it separate from Brahman (which would imply duality). Rather, the world is Brahman's own Shakti in manifestation—the infinite appearing as finite while remaining infinite, the unchanging appearing as change while remaining unchanging.

The recognition that “Brahman and Shakti are one” reveals why worship of Devi is direct worship of Brahman [11]. Shakti is not a separate power that Brahman possesses but the very nature of Brahman itself. Just as wetness is not separate from water but is water's essential nature, Shakti is not separate from Brahman but is Brahman's essential creative nature. To recognize Shakti is to recognize Brahman; to worship Devi is to recognize one's own essential nature as the creative power of consciousness itself.

This integration also explains why the path of devotion (bhakti) and the path of knowledge (jnana) ultimately converge. In mature devotion, the devotee recognizes that the beloved divine is not separate from their own deepest Self. In mature knowledge, the knower recognizes that pure awareness is not static but is inherently creative and dynamic. Both paths lead to the same recognition: the individual self and the cosmic Self are one reality appearing as two through the play of consciousness knowing itself.

The Illusion of Separation: How Idol Worship Becomes a Deterrent

The Trap of External Forms

The human mind, in its attempt to grasp the infinite, naturally seeks tangible forms through which to approach the divine. This tendency, while understandable and even necessary for those beginning spiritual practice, contains within it the seeds of a profound spiritual trap. When forms are mistaken for the reality they are meant to represent, they become obstacles rather than aids to realization.

The fundamental problem with idol worship lies not in the use of forms per se, but in the unconscious assumption of separation that underlies the practice. When a devotee approaches an idol as the dwelling place of divinity, they implicitly accept that divinity exists “there” in the form while they exist “here” as a separate individual seeking connection. This creates what Advaita Vedanta calls bheda-buddhi—the intellect that perceives difference where there is actually only one reality [12].

This perception of difference is not merely an intellectual error but a lived experience that shapes every aspect of spiritual practice. The devotee experiences themselves as lacking something that the idol possesses, as needing something that must be obtained through proper worship, as being in a state of separation that can only be bridged through correct ritual performance. Each prayer becomes a reinforcement of the gap between seeker and sought, each offering a confirmation of the devotee's sense of incompleteness.

The Katha Upanishad warns against this trap when it declares that “the Self cannot be attained by study of scriptures, nor by intelligence, nor by much learning” [13]. While this verse specifically mentions scriptures and learning, the same principle applies to external forms of worship. The Self cannot be attained through external means because it is not external. It is the very awareness through which all external seeking occurs.

Consider the psychological dynamics at play in conventional idol worship. The devotee approaches the temple or shrine with a sense of anticipation, believing that proximity to the sacred form will provide access to divine grace or blessing. This creates a subtle but profound reinforcement of the belief that the divine exists in some places and not others, is accessible at some times and not others, requires specific conditions and preparations for contact. Each successful experience of devotion paradoxically reinforces the belief that these experiences come from the external form rather than from the devotee's own essential nature.

The tragedy of this misunderstanding is that it obscures the very truth that authentic spiritual practice is meant to reveal. The peace experienced in the temple is not produced by the idol but is the natural state of consciousness when the mind becomes still. The sense of connection felt during worship is not a bridging of separation but a temporary dropping of the belief in separation. The love that arises in devotion is not directed toward something external but is the recognition of one's own essential nature as love itself.

Swami Sivananda's observation that idol worship serves as “a support for the neophyte” and “a prop of his spiritual childhood” points to both the utility and the limitation of external forms [14]. Like training wheels on a bicycle, external supports can be helpful for those learning to balance, but they become obstacles when the practitioner is ready to ride freely. The problem arises when the training wheels are mistaken for the bicycle itself, when the support is confused with the goal.

The Mandukya Upanishad provides a profound analysis of this confusion through its description of the four states of consciousness. In the waking state (jagrat), consciousness appears to be limited by and dependent upon external objects. In the dream state (swapna), consciousness creates its own objects of experience. In deep sleep (sushupti), consciousness exists without any objects at all. The fourth state (turiya) is the recognition that consciousness itself is the constant reality underlying all three states [15]. Idol worship, when it reinforces identification with the waking state alone, prevents the recognition of consciousness as the fundamental reality that is present in all states and dependent upon none.

The Dependency on Priests and External Authority

Of course. Here is the provided text with the essential elements emphasized in bold.One of the most insidious aspects of conventional religious practice is the creation of a priestly class that positions itself as necessary intermediary between the devotee and the divine. This system, while often arising from genuine intentions to preserve and transmit spiritual knowledge, inevitably creates a form of spiritual dependency that directly contradicts the fundamental truth of non-dual realization.

When devotees are taught that proper worship requires specific rituals performed by qualified priests, that mantras must be received through formal initiation, that divine grace flows through institutional channels, they are being systematically conditioned to believe that their direct relationship with the divine is insufficient or impossible. This conditioning operates at both conscious and unconscious levels, creating a deep-seated belief that spiritual realization requires external validation and mediation.

The psychological impact of this dependency extends far beyond the religious sphere. It creates what might be called “spiritual learned helplessness”—the belief that one is inherently incapable of direct spiritual experience and must rely upon others for access to the divine. This belief becomes self-fulfilling as devotees increasingly doubt their own capacity for direct realization and become more dependent upon external authorities for spiritual guidance and validation.

The Kena Upanishad directly challenges this dependency when it reveals that Brahman is “that which is not expressed by speech but by which speech is expressed” [16]. This points to the recognition that the ultimate reality is not something that can be transmitted through words, rituals, or external means but is the very consciousness that makes all communication possible. No priest, no matter how learned or accomplished, can give another person their own consciousness. No ritual, no matter how perfectly performed, can create what is already present as the ground of all experience.

The tragedy of priestly mediation is that it obscures the most fundamental teaching of all authentic spiritual traditions: that the divine is not separate from the seeker. When the Chandogya Upanishad declares “Tat tvam asi”—“That thou art”—it is pointing directly to the recognition that what appears as the individual self and what appears as the cosmic Self are one reality [17]. No external authority can validate this recognition because it is the very ground from which all authority arises.

The system of priestly mediation also creates what might be called “spiritual materialism”—the belief that spiritual advancement can be purchased through donations, that divine favor can be earned through elaborate offerings, that liberation can be achieved through accumulation of religious merit. This transforms the spiritual path from a process of Self-discovery into a form of cosmic commerce where the devotee attempts to negotiate with the divine through material transactions.

The Isha Upanishad warns against this materialistic approach when it declares, “Those who worship the unmanifested alone fall into darkness, but those who worship only the manifested fall into greater darkness” [18]. The “greater darkness” of worshipping only the manifested includes the belief that external forms and rituals are sufficient for realization. This creates a spiritual materialism that is more subtle but ultimately more binding than ordinary materialism because it co-opts the very impulse toward liberation and redirects it toward dependency.

The Limitations of Rituals and Mantras

The elaborate ritual systems that have developed around Devi worship, while containing profound symbolic wisdom, often become ends in themselves rather than means to Self-realization. The performance of complex ceremonies, the recitation of lengthy mantras, the observance of intricate protocols—all of these can create a sense of spiritual accomplishment while actually reinforcing the very ego-structure that authentic spirituality seeks to dissolve.

The fundamental limitation of ritual practice lies in its operation within the realm of maya—the apparent world of multiplicity and change. Rituals involve the manipulation of objects, the performance of actions, the achievement of results. They operate according to the logic of cause and effect, effort and attainment, practice and progress. While this logic is perfectly valid within the relative realm of experience, it becomes an obstacle when applied to the recognition of what is already present and complete.

The Bhagavad Gita addresses this limitation when Krishna declares, “For one who has been elevated in yoga, work is said to be the means; for one who is already elevated in yoga, cessation of all material activities is said to be the means” [19]. This verse points to the recognition that practices which are helpful at one stage of development can become obstacles at another stage. The devotee who has recognized their essential nature as pure consciousness no longer needs to perform actions to achieve what they already are.

The problem with mantra recitation, when approached mechanically, is that it can become a form of spiritual automation that bypasses rather than cultivates awareness. The repetition of sacred sounds, while potentially powerful when done with understanding, often becomes a way of occupying the mind rather than investigating its nature. The devotee may spend hours reciting mantras while remaining completely identified with the mental commentary that judges the practice, evaluates progress, and maintains the sense of being a separate individual performing spiritual exercises.

The Mandukya Upanishad reveals the deeper significance of the sacred syllable Om not as a sound to be repeated but as a pointer to the structure of consciousness itself [20]. The three letters A-U-M represent the three states of waking, dreaming, and deep sleep, while the silence that follows represents the fourth state (turiya) that is the witness of all three. When Om is understood in this way, its recitation becomes a form of Self-inquiry rather than mechanical repetition.

The limitation of external rituals becomes particularly clear when we consider their relationship to the ego-structure. Most rituals are designed to be performed by someone—they require a sense of personal agency, individual effort, and separate identity. The very act of performing a ritual reinforces the belief that there is someone who needs to do something to achieve something else. This directly contradicts the fundamental recognition of non-dual realization: that there is no separate individual who needs to achieve anything because what appears as the individual is already the very reality being sought.

The Ashtavakra Gita expresses this recognition with startling directness: “You are not the body, nor is the body yours. You are not the doer, nor the enjoyer. You are consciousness itself, the eternal witness. Live happily” [21]. From this perspective, the question of performing rituals becomes irrelevant because there is no separate individual to perform them and no separate goal to be achieved through their performance.

This does not mean that rituals are inherently wrong or should be abandoned by everyone. For those whose minds require structure and activity, ritual practice can serve as a form of meditation that gradually refines attention and cultivates devotion. The key is to understand rituals as temporary expedients rather than ultimate practices, as fingers pointing to the moon rather than the moon itself. When rituals are performed with this understanding, they can serve the process of Self-inquiry. When they are performed with the belief that they are necessary for realization, they become obstacles to the very recognition they are meant to facilitate.

The Divine Mother Within: Recognizing Your Identity with Brahman

The Inner Shakti: Devi as Your True Self

The most profound shift in spiritual understanding occurs when the seeker recognizes that what they have been seeking outside themselves has been the very ground of their own being all along. The Divine Mother, rather than being a cosmic personality to be approached through external worship, is revealed as the very consciousness through which all seeking occurs. This recognition transforms the entire spiritual path from a journey toward something distant to an awakening to what is most intimate and immediate.

The Devi Gita points to this recognition when it declares, “My true Self is known as pure consciousness, the highest intelligence, the one supreme Brahman” [22]. The crucial word here is “My”—when Devi speaks of Her true Self, She is not referring to a personal identity separate from the devotee's true Self. The pure consciousness that is Her essence is the same pure consciousness that is reading these words, contemplating these ideas, and experiencing this very moment of awareness.

This pure consciousness is not a thing or entity that can be objectified or grasped. It is the very subjectivity through which all objects appear. It is not something you have but what you are. It is not something you can attain because you cannot step outside of it to acquire it. It is not something you can lose because it is the very awareness of loss. It is not something you can improve because it is already perfect and complete.

The recognition of consciousness as one's true nature dissolves the fundamental assumption that underlies all seeking: the belief that you are something other than what you are seeking. When this assumption is seen through, the entire structure of spiritual practice is transformed. Instead of trying to get somewhere else, you recognize where you already are. Instead of trying to become something different, you recognize what you have always been. Instead of trying to achieve a special state, you recognize the ordinary awareness that is present in all states.

The Ribhu Gita expresses this recognition with remarkable clarity: “There is no individual soul, no God, no world, no teacher, no student, no bondage, no liberation. There is only the Self, appearing as all these through its own power of manifestation” [23]. This is not a philosophical position but a direct description of what is revealed when the mind's habitual patterns of seeking and grasping are seen through.

The Divine Mother as inner Shakti is not a subtle energy or mystical force that can be cultivated through practices. She is the very power by which consciousness appears as the world of experience while never ceasing to be pure consciousness. She is the creative intelligence by which the one appears as many, the infinite appears as finite, the eternal appears as temporal. To recognize Her is to recognize that what appears as your individual life is actually the cosmic life appearing as individuality.

This recognition has profound implications for how we understand personal identity and individual experience. What appears as your thoughts, emotions, sensations, and perceptions are not modifications of a separate individual consciousness but are the Divine Mother's own creative expression appearing as personal experience. Your joys and sorrows, your insights and confusions, your spiritual experiences and ordinary moments—all of these are Her play (lila) appearing within Her own being.

The Spanda Karika reveals this understanding when it declares, “The entire universe is nothing but the vibration (spanda) of consciousness” [24]. This vibration is not something that consciousness does but is consciousness itself in its dynamic aspect. Just as waves are not separate from the ocean but are the ocean in motion, all experience is not separate from consciousness but is consciousness in manifestation.

The Path of Self-Inquiry (Atma-Vichara)

Of course. Here is the provided text with the essential elements emphasized in bold.The most direct method for recognizing one's identity with Brahman is the practice of Self-inquiry (atma-vichara), systematized by Sri Ramana Maharshi but rooted in the most ancient Vedantic teachings. This practice involves the persistent investigation of the question “Who am I?” not as an intellectual exercise but as a direct exploration of the nature of the one who is asking the question.

The genius of Self-inquiry lies in its recognition that the seeker and the sought are not separate. Every spiritual practice assumes someone who practices and something to be achieved through practice. Self-inquiry reveals that the one who seeks is already what is being sought. The “I” that asks “Who am I?” is the very reality that the question is designed to reveal.

The practice begins with the recognition that you are not what you appear to be. You are not the body because you are aware of the body. You are not the thoughts because you are aware of thoughts. You are not the emotions because you are aware of emotions. You are not the personality because you are aware of the personality. Through this process of negation (neti neti), attention is withdrawn from all objects of awareness and directed toward the awareness itself.

But Self-inquiry does not stop with negation. Having recognized what you are not, the question becomes: what is this awareness that is aware of all these things? This awareness cannot be objectified because it is the subject of all objectification. It cannot be described because it is that which makes all description possible. It cannot be attained because it is that which makes all attainment possible.

The Ashtavakra Gita points to this recognition: “How can I salute the Self? It cannot be held or abandoned. It pervades the universe, yet is beyond space. It is the Self alone that appears as the universe” [25]. This verse reveals that the Self is not something to be found but is what is already present as the very seeking itself.

The practice of Self-inquiry naturally dissolves the ego-structure that maintains the illusion of separation. The ego is essentially the belief that you are a separate individual located in a body, having experiences, and needing to achieve something. Self-inquiry reveals that there is no separate individual—there is only consciousness appearing as individuality. There is no one located in a body—there is only consciousness appearing as embodiment. There is no one having experiences—there is only consciousness appearing as experience.

This dissolution is not a destruction but a recognition. The ego is not eliminated but is seen to be a case of mistaken identity. Just as the recognition that a rope is not a snake does not destroy the rope, the recognition that you are not a separate individual does not destroy the appearance of individuality. It simply reveals what was always true: that individuality is consciousness appearing as limitation while never actually being limited.

The Vivekachudamani describes this process: “The ego-sense is destroyed by the constant practice of fixing the mind on the Self. When the ego is destroyed, all desires are destroyed, and one attains the supreme peace” [26]. The “destruction” referred to here is not an annihilation but a seeing-through of what was never actually real.

Meditation as Direct Realization

True meditation is not a practice performed by someone but the recognition of what you already are. It is not a method for achieving a special state but the acknowledgment of the awareness that is present in all states. It is not something you do but what you are when all doing ceases.

The conventional understanding of meditation as a technique to be practiced by an individual seeking to achieve a particular result is based on the same dualistic assumption that underlies external worship. It assumes someone who meditates, something to be achieved through meditation, and a process by which the achievement occurs. While this approach can be helpful for those whose minds require structure and activity, it ultimately reinforces the very sense of separation that authentic meditation is meant to dissolve.

In the context of Devi worship, meditation becomes the recognition that the Divine Mother is not an object of meditation but the very awareness in which all meditation occurs. She is not something to be visualized or contemplated but the consciousness that makes all visualization and contemplation possible. She is not a presence to be invoked but the presence that is already present as your own being.

The Vijnanabhairava Tantra presents 112 methods of meditation, each designed to reveal the same fundamental truth: that consciousness is already present and complete [27]. These methods are not techniques for producing consciousness but ways of recognizing what is already the case. They are fingers pointing to the moon of pure awareness that is never absent from any experience.

One of the most direct approaches involves simply resting as the awareness that is aware of whatever is arising in this moment. Without trying to change, improve, or transcend your present experience, simply recognize the awareness in which all experience appears. This awareness is not personal—it does not belong to you. Rather, you appear within it as a temporary modification of its infinite nature.

The practice of meditation as Self-recognition naturally leads to what the tradition calls sahaja samadhi—the natural state of absorption in the Self that continues even during ordinary activities [28]. This is not a special state to be achieved but the recognition that all states appear within the same unchanging awareness. Whether you are thinking or not thinking, active or still, happy or sad, the awareness in which all these experiences appear remains constant and unaffected.

The Ashtavakra Gita describes this natural state: “I am not the mind, intellect, ego, or memory. I am not the ears, tongue, nose, or eyes. I am not space, earth, fire, water, or air. I am consciousness and bliss. I am Shiva” [29]. This is not a philosophical statement but a direct description of what is revealed when identification with temporary experiences ceases.

In this recognition, the distinction between meditation and daily life dissolves. Every moment becomes an opportunity to recognize the Divine Mother as your own essential nature. Every experience becomes a manifestation of Her creative power. Every breath becomes a celebration of the consciousness that makes all experience possible.

The awakening of Kundalini, often described in elaborate mystical terms, is simply the recognition of consciousness as the fundamental reality. The various chakras and energy centers are not locations in a subtle body but aspects of the one consciousness appearing as different qualities of experience. The journey of Kundalini from the base of the spine to the crown of the head is the recognition that what appears as individual consciousness is actually cosmic consciousness appearing as individuality.

This recognition is not an achievement but a homecoming. It is not the attainment of something new but the acknowledgment of what has always been present. It is not a special experience but the recognition that all experience, including the most ordinary moments, is the Divine Mother's own creative expression appearing within Her own being.

Jivanmukti: Liberation While Embodied

The Nature of Living Liberation

Jivanmukti—liberation while still embodied—represents the ultimate fulfillment of spiritual realization within the context of human existence. Unlike videhamukti (liberation at death) or kramamukti (gradual liberation after death), jivanmukti is the recognition that liberation is not a future attainment but a present reality that can be acknowledged while still appearing to live in a physical body [30].

The jivanmukta (liberated being) has realized that what they took themselves to be—a separate individual bound by the limitations of body, mind, and circumstance—was a case of mistaken identity. They have recognized their true nature as the infinite consciousness in which all experience appears, including the experience of embodiment. This recognition does not eliminate the appearance of individuality but reveals it to be a temporary play of consciousness rather than a fundamental reality.

The profound significance of jivanmukti lies in its demonstration that liberation is not dependent upon the dissolution of the body or the cessation of experience. The Jivanmukti Viveka of Vidyaranya explains that the jivanmukta continues to appear to live, act, and interact in the world while remaining established in the recognition of their true nature as Brahman [31]. They eat when hungry, sleep when tired, and respond to circumstances as they arise, but without the sense of being a separate individual who is affected by these experiences.

This state is not a detached withdrawal from life but a complete intimacy with existence that is no longer filtered through the lens of personal identity. The jivanmukta experiences the full range of human emotions and sensations but without the overlay of psychological suffering that comes from believing these experiences define or limit their essential nature. Joy and sorrow arise and pass away like weather patterns in the sky of consciousness, touching but not disturbing the fundamental peace of their being.

The Bhagavad Gita describes this state through Krishna's teaching about the sthitaprajna—one who is established in wisdom: “As a person puts on new garments, giving up old ones, the soul similarly accepts new material bodies, giving up the old and useless ones” [32]. This verse points to the recognition that consciousness itself is never born and never dies—only the forms through which it appears are subject to change.

The jivanmukta has realized what the Devi Gita declares: “Being Brahman, one who knows Brahman, attains Brahman.” They are Brahman (their essential nature has never been otherwise), they know Brahman (they recognize this truth directly), and they have attained Brahman (the illusion of separation has dissolved). This is not a linear progression but three aspects of the same recognition occurring simultaneously.

Beyond the Three Gunas and Maya

The liberated being has transcended identification with the three gunas—sattva (harmony), rajas (activity), and tamas (inertia)—that govern all phenomenal experience. While these qualities continue to operate through their apparent body-mind, the jivanmukta is no longer identified with their fluctuations. They remain as the witness consciousness in which all qualities appear and disappear.

The Bhagavad Gita describes this transcendence: “One who is unattached to the fruits of his work and who works as he is obligated is in the renounced order of life, and he is the true mystic, not he who lights no fire and performs no duty” [33]. This verse reveals that true renunciation is not the abandonment of activity but the abandonment of the sense of being the doer of activity.

The jivanmukta has also transcended maya—not by escaping from the world of appearance but by recognizing its true nature. Maya is not an illusion in the sense of being unreal, but rather the creative power by which the one appears as many. The liberated being recognizes that what appears as the multiplicity of experience is actually the play of their own essential nature as consciousness.

This recognition transforms the entire relationship to experience. What previously appeared as bondage is now seen as freedom, what appeared as limitation is now seen as the infinite appearing as limitation, what appeared as suffering is now seen as consciousness exploring its own creative potential. The Ashtavakra Gita expresses this transformation: “Bondage is when the mind desires, grieves, or makes efforts. Liberation is when the mind does not desire, grieve, or make efforts” [34].

The jivanmukta lives in what might be called “divine ordinariness”—fully engaged with the practical aspects of life while never losing sight of the extraordinary truth of their essential nature. They may appear to others as completely normal human beings, yet they abide in a recognition that transforms every moment into a celebration of consciousness knowing itself.

The Fulfillment of Devi Gita 7.32

Of course. Here is the final part of the text with the essential elements emphasized in bold.The verse “Being Brahman, one who knows Brahman, attains Brahman” finds its complete fulfillment in the state of jivanmukti. Each aspect of this declaration represents a dimension of the liberated being's realization.

“Being Brahman” (brahman san) is the ontological recognition that consciousness is not produced by the body or brain but is the fundamental reality in which all experience appears. The jivanmukta has realized that they have never been anything other than Brahman—not as a philosophical belief but as a lived reality. They recognize that what appeared as individual consciousness was always cosmic consciousness appearing to itself as individuality.

This recognition eliminates the fear of death because it reveals that what you truly are was never born and therefore cannot die. The body may appear and disappear, thoughts may come and go, experiences may arise and pass away, but the awareness in which all these appearances occur is eternal and unchanging. The Katha Upanishad confirms this recognition: “The Self is not born, nor does it die. It did not come from anywhere, nor did anything come from it. It is unborn, eternal, permanent, and ancient” [35].

“One who knows Brahman” (brahma-vid) points to the epistemological aspect of realization—the direct, immediate recognition of one's true nature. This knowing is not intellectual understanding but aparoksha-jnana—direct, immediate knowledge that is self-evident and requires no external validation. It is the difference between knowing about water and being wet, between studying fire and being burned.

The jivanmukta knows Brahman not as an object of knowledge but as the very subject of all knowing. They recognize that every act of perception, every moment of awareness, every instance of understanding is Brahman knowing itself through the apparent limitation of individual consciousness. The knower, the process of knowing, and the known are revealed to be one reality appearing as three.

“Attains Brahman” (brahmaiva bhavati) reveals the soteriological dimension—the complete dissolution of the sense of separation that constitutes liberation. The jivanmukta has not acquired something new but has recognized what was always present. They have not become Brahman but have stopped believing they were ever anything else.

This attainment is not a future goal but a present recognition. It does not require years of practice or elaborate preparations, though these may serve to prepare the mind for recognition. It can occur in any moment when the habitual patterns of seeking and grasping are seen through. The Mandukya Upanishad points to this immediacy when it declares that the fourth state (turiya) is “not an object of knowledge” but is “the very Self” [36].

The jivanmukta embodies the complete integration of these three aspects. They live as Brahman (being), recognize themselves as Brahman (knowing), and have realized their identity as Brahman (attaining). This is not a static achievement but a dynamic recognition that continues to deepen and express itself through every moment of apparent existence.

In this state, the worship of Devi is revealed in its ultimate form—not as the devotion of a separate individual to an external deity, but as the Self celebrating its own nature through the play of devotion. The jivanmukta may continue to participate in worship, but they do so with the recognition that there is only one consciousness appearing as both the worshipper and the worshipped. Their entire life becomes a form of worship—not seeking to attain the divine but expressing the divine that they have recognized themselves to be.

The state of jivanmukti thus represents the complete fulfillment of the spiritual path. It is the recognition that what was sought through external means was always present as one's own essential nature. It is the end of seeking because it is the recognition that the seeker and the sought were never separate. It is the beginning of true life because it is the end of the illusion that life is limited by birth and death.

This recognition is available in every moment to every apparent individual because it is not dependent upon circumstances, practices, or attainments. It requires only the willingness to investigate the nature of the one who is reading these words, thinking these thoughts, and experiencing this moment of awareness. In that investigation, the Divine Mother reveals herself as what you have always been, and liberation is recognized as what you have always had.

Practical Guidance: From Ritual to Realization

Transcending External Worship

The transition from external worship to Self-realization is not a rejection of devotional practices but a deepening understanding of their true purpose and ultimate limitation. For those who have been engaged in traditional forms of Devi worship, this transition requires both wisdom and compassion—wisdom to recognize when external supports are no longer serving their intended purpose, and compassion for the part of oneself that may feel reluctant to release familiar forms of practice.

The key principle in this transition is to use external forms as stepping stones rather than destinations. When approaching an idol or image of Devi, instead of seeing it as the location of divinity, recognize it as a reminder of your own essential nature. When reciting mantras, instead of believing that the repetition itself produces spiritual benefit, use the practice as an opportunity to investigate the awareness in which the sounds appear and disappear.

The Kularnava Tantra provides guidance for this transition: “The worship of the external form is for beginners. The worship of the internal form is for the advanced. The worship of the formless is for the perfect. But the wise know that all three are one” [37]. This verse reveals that the different approaches to worship are not contradictory but represent different levels of understanding of the same truth.

For those ready to move beyond external forms, the practice becomes one of constant Self-inquiry. In every moment of experience, the question arises: “Who is aware of this?” Whether you are experiencing joy or sorrow, clarity or confusion, the presence of thoughts or their absence, there is always the awareness in which these experiences appear. This awareness is not personal—it is the Divine Mother herself appearing as your capacity to be conscious.

The transition also involves recognizing the difference between devotion and dependency. True devotion is the love that arises when you recognize your beloved as your own Self. Dependency is the belief that you need something external to complete or fulfill you. Devotion leads to union; dependency perpetuates separation. The Narada Bhakti Sutra distinguishes between apara bhakti (lower devotion) which seeks something from the divine, and para bhakti (higher devotion) which seeks nothing because it recognizes no separation [38].

Cultivating Inner Awareness

The cultivation of inner awareness is not a practice in the conventional sense but a growing recognition of what is already present. It involves a gradual shift of attention from the contents of consciousness to consciousness itself, from the experiences that arise and pass away to the awareness in which all experience appears.

This cultivation can begin with simple recognition exercises throughout the day. When you wake in the morning, before engaging with thoughts about the day ahead, simply notice the awareness that is aware of waking. When you eat, notice not just the taste and texture of food but the consciousness that makes all sensation possible. When you interact with others, recognize that the same awareness that looks out through your eyes is looking out through theirs.

The practice of witnessing (sakshi bhava) is particularly valuable in this cultivation. Instead of being identified with the various roles you play—parent, professional, spiritual seeker—recognize yourself as the witness of all these roles. The witness is not another role but the consciousness in which all roles appear. It is not affected by the success or failure of any particular role because it is the unchanging background against which all change occurs.

The Ashtavakra Gita describes this witnessing: “You are the one witness of everything and are always free. Your only bondage is seeing the witness as something other than this” [39]. This verse points to the recognition that freedom is not something to be achieved but is your very nature as the witness consciousness.

Another valuable approach is the practice of nididhyasana—contemplative meditation on the truth of your essential nature. This involves repeatedly returning attention to the recognition “I am pure consciousness” or “I am the Divine Mother appearing as individual awareness.” This is not an affirmation or positive thinking but a direct investigation of what these statements point to in your immediate experience.

The cultivation of inner awareness naturally leads to what might be called “seamless recognition”—the continuous acknowledgment of your true nature that persists through all activities and experiences. This is not a special state that comes and goes but the recognition of what is always present. Whether you are engaged in work, relationships, or solitary reflection, there is always the same awareness present as the ground of all experience.

Living the Truth of Non-Duality

The ultimate test of spiritual understanding is not the ability to have profound experiences or to articulate sophisticated philosophy, but the capacity to live from the recognition of non-dual truth in the midst of ordinary circumstances. This involves a fundamental reorientation of how you relate to yourself, others, and the world around you.

When you recognize yourself as consciousness appearing as an individual, your relationship to personal challenges and difficulties is transformed. Problems are no longer seen as obstacles to your happiness or spiritual progress but as opportunities for consciousness to explore its own creative potential. The Yoga Vashishta expresses this understanding: “The world is as you see it. If you see it as bondage, it becomes bondage. If you see it as liberation, it becomes liberation” [40].

This recognition also transforms your relationship to others. When you see clearly that the same consciousness that appears as your individual awareness also appears as every other person's awareness, compassion arises naturally. This is not a moral imperative imposed from outside but the spontaneous expression of recognizing others as yourself. Service to others becomes service to your own Self appearing in different forms.

The practice of seeing Devi in all experiences becomes a natural expression of this recognition. Every person you encounter is the Divine Mother appearing in that particular form. Every situation you face is Her creative expression. Every emotion that arises is Her energy moving through the apparent limitation of individual consciousness. This is not a visualization exercise but a recognition of what is actually the case when seen clearly.

Living from non-dual recognition also involves what might be called “effortless effort”—engaging fully with life while remaining unattached to outcomes. The Bhagavad Gita describes this as nishkama karma—action without attachment to results [41]. When you recognize that you are not the doer of actions but the consciousness in which all action appears, you can engage completely with whatever needs to be done while remaining free from the anxiety and stress that come from believing you are responsible for controlling outcomes.

This way of living naturally expresses the qualities that are traditionally associated with spiritual realization: peace, love, compassion, wisdom, and joy. These are not qualities that you develop or cultivate but are the natural expression of consciousness when it is no longer filtered through the belief in separation. They arise spontaneously when the obstacles to their expression—primarily the sense of being a separate, limited individual—are removed.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Worship - Being What You Are

As we reach the culmination of this exploration into the profound truth that worshiping Devi is direct worship of Brahman, we find ourselves not at the end of a journey but at the recognition that there was never anywhere to go. The entire spiritual path, with all its practices, struggles, and insights, is revealed to be consciousness exploring its own nature through the apparent limitation of individual seeking.

The central message that emerges from our investigation is both simple and revolutionary: you are already what you are seeking. The Divine Mother that appears to be the object of worship is actually the subject of all worship—the very consciousness through which all seeking occurs. The Brahman that seems to be the ultimate goal of spiritual practice is the very awareness that makes all practice possible. The liberation that appears to be a future attainment is the ever-present nature of what you are in this very moment.

This recognition does not diminish the value of the spiritual journey but reveals its true purpose. Every practice, every insight, every moment of devotion has served to prepare the mind for this ultimate recognition. The external worship of idols, the recitation of mantras, the performance of rituals—all of these have played their role in refining attention and cultivating the devotion that ultimately turns inward to discover its own source.

The tragedy of conventional religious practice lies not in its methods but in its misunderstanding of its own purpose. When external forms are mistaken for ultimate reality, when priests are believed to be necessary intermediaries, when rituals are thought to produce what is already present, the very practices meant to reveal truth become obstacles to its recognition. The seeker becomes trapped in an endless cycle of seeking, never recognizing that what they seek is the very one who is seeking.

The Devi Gita's declaration that “Being Brahman, one who knows Brahman, attains Brahman” reveals the ultimate futility and ultimate fulfillment of all spiritual seeking. It is futile because there is no separate individual who can attain what they already are. It is fulfilling because in the recognition of this futility, the truth of what you are is revealed. You are Brahman seeking itself, knowing itself, and recognizing itself through the play of apparent individuality.

The path from ritual to realization is not a rejection of devotion but its ultimate fulfillment. When you recognize that there is only one consciousness appearing as both the devotee and the divine, worship becomes celebration rather than supplication. When you see that the Divine Mother is not separate from your own essential nature, every moment becomes an opportunity for recognition rather than seeking. When you understand that Brahman is not a distant goal but your immediate reality, spiritual practice becomes an expression of what you are rather than an attempt to become something else.

The state of jivanmukti—liberation while embodied—is not a special achievement reserved for a few advanced souls but the natural condition that is revealed when the illusion of separation is seen through. It is available in this moment to anyone willing to investigate the nature of their own awareness. It requires no special qualifications, no years of preparation, no external validation. It requires only the willingness to look directly at what is most obvious and immediate: the consciousness that is aware of these very words.

For those who have been engaged in traditional forms of Devi worship, this recognition does not require abandoning all familiar practices but understanding their true significance. The idol in the temple can continue to serve as a reminder of your own divine nature. The mantras can continue to be recited as celebrations of the consciousness that makes all sound possible. The rituals can continue to be performed as expressions of devotion to your own Self appearing as the cosmic Self.

The key is to remember that all external forms are fingers pointing to the moon of your own essential nature. They are valuable as long as they serve this pointing function and become obstacles when they are mistaken for the moon itself. The wise devotee uses forms when they are helpful and releases them when they are no longer needed, always keeping attention focused on what the forms are meant to reveal.

The ultimate worship of the Divine Mother is simply being what you are—pure consciousness appearing as individual experience while never ceasing to be infinite and free. In this recognition, every breath becomes a prayer, every heartbeat becomes a mantra, every moment of awareness becomes a celebration of the one reality appearing as the many while never ceasing to be one.

This is the invitation that the Divine Mother extends in every moment: to recognize yourself as what you have always been, to cease the seeking that perpetuates the illusion of separation, and to live from the recognition that there is only one consciousness appearing as all experience. In this recognition, the question of worship dissolves because there is no one separate to worship and nothing separate to be worshipped. There is only the Self celebrating its own nature through the infinite creativity of its own being.

The journey from external worship to Self-realization is ultimately a journey from believing you are a wave seeking the ocean to recognizing that you are the ocean appearing as a wave. The wave was never separate from the ocean, never needed to find the ocean, never could be anything other than the ocean. In the same way, you have never been separate from Brahman, never needed to find Brahman, never could be anything other than Brahman appearing as the beautiful limitation of individual consciousness.

This is the final teaching, the ultimate recognition, the end of all seeking: you are That which you seek, you have always been That which you seek, and you will always be That which you seek. The Divine Mother's greatest gift is not the granting of desires or the bestowing of blessings, but the revelation of this eternal truth. In recognizing this truth, all worship is fulfilled, all seeking comes to rest, and the eternal celebration of consciousness knowing itself begins.

References

[1] ↑ Lalita Sahasranama, Names 246-247: Yajamana-svarupini and Pujya

[2] ↑ Devi Gita 7.32: "brahman san brahma-vid brahmaiva bhavati"

[3] ↑ Devi Gita 4.12: "mama satyam param rupam chid-ananda-param padam"

[4] ↑ Devi Gita 1.5: "aham eva asam evagre nanyat yat sad-asat param"

[5] ↑ Lalita Sahasranama Commentary by Bhaskararaya

[6] ↑ Lalita Sahasranama, Names 256, 114, 366

[7] ↑ Lalita Sahasranama, Dhyana Sloka reference to Pancha-Brahma

[8] ↑ Lalita Sahasranama Commentary on Maya-related names

[9] ↑ Saundarya Lahari by Adi Shankaracharya

[10] ↑ Brahma Sutra 1.4.23: "upadana-nimitta-karanatva"

[11] ↑ Shakti-Shiva Advaita principle in Kashmir Shaivism

[12] ↑ Vivekachudamani, Verse 210: "bheda-buddhi-vinashanam"

[13] ↑ Katha Upanishad 1.2.23: "nayam atma pravacanena labhyo"

[14] ↑ Swami Sivananda, "Idol Worship" in Divine Life Society publications

[15] ↑ Mandukya Upanishad, Verses 3-7: Four states analysis

[16] ↑ Kena Upanishad 1.5: "yad vachanaabhyuditam yena vag abhyudyate"

[17] ↑ Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7: "tat tvam asi shvetaketo"

[18] ↑ Isha Upanishad, Verse 12: "andham tamah pravisanti"

[19] ↑ Bhagavad Gita 6.3: "arurukshor muner yogam karma karanam uchyate"

[20] ↑ Mandukya Upanishad, Verses 8-12: Om analysis

[21] ↑ Ashtavakra Gita 1.4: "na tvam deho na te deho"

[22] ↑ Devi Gita 4.12: Pure consciousness declaration

[23] ↑ Ribhu Gita 26.20: Non-dual recognition

[24] ↑ Spanda Karika 1.1: "yatra chaikasminn akshare"

[25] ↑ Ashtavakra Gita 2.20: "katham namami atmaanam"

[26] ↑ Vivekachudamani, Verse 285: Ego dissolution

[27] ↑ Vijnanabhairava Tantra: 112 meditation methods

[28] ↑ Sahaja Samadhi description in Advaita texts

[29] ↑ Ashtavakra Gita 1.5: "na mano buddhir ahankar"

[30] ↑ Jivanmukti classification in Advaita Vedanta

[31] ↑ Jivanmukti Viveka by Vidyaranya

[32] ↑ Bhagavad Gita 2.22: "vasamsi jirnani yatha vihaya"

[33] ↑ Bhagavad Gita 6.1: "anashritah karma-phalam"

[34] ↑ Ashtavakra Gita 1.15: "iccha-dvesha-sukha-duhkha"

[35] ↑ Katha Upanishad 1.2.18: "na jayate mriyate va"

[36] ↑ Mandukya Upanishad, Verse 7: Turiya description

[37] ↑ Kularnava Tantra 9.32: Levels of worship

[38] ↑ Narada Bhakti Sutra 54: Para and Apara Bhakti

[39] ↑ Ashtavakra Gita 1.12: "tvam sakshi sarva-bhutanam"

[40] ↑ Yoga Vashishta 3.9.32: World as perception

[41] ↑ Bhagavad Gita 3.19: "nishkama karma" principle

---

*This document represents a synthesis of traditional Advaitic and Shakta teachings with contemporary understanding of non-dual realization. It is offered as a pointer to the truth that can only be recognized directly through Self-inquiry and the grace of the Divine Mother appearing as one's own essential nature.*

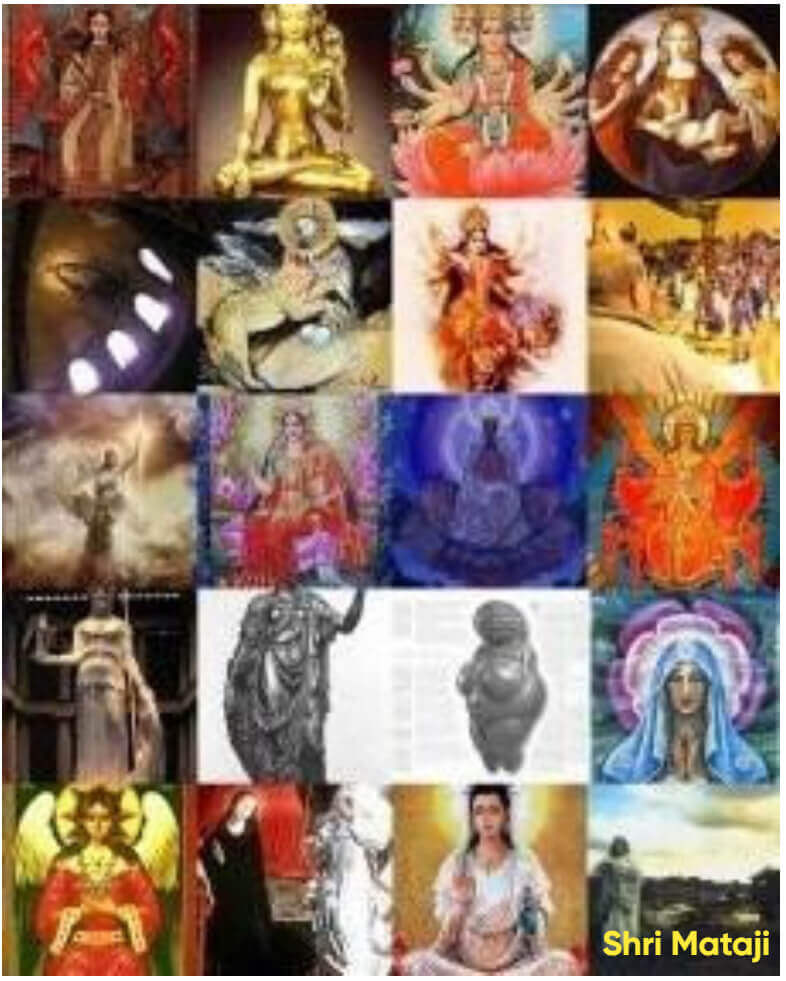

NATURE OF THE DIVINE MOTHER OR HOLY SPIRIT

The Goddess is Supreme Feminine Guru

Worshiping Devi is Direct Worship of Brahman

MahaDevi Research Paper (PDF)

The Supremacy of the MahaDevi Across All Faiths

The Divine Feminine in China

The Indian Religion of Goddess Shakti

The Divine Feminine in Biblical Wisdom Literature

Divine Feminine Unity in Taoism and Hinduism

Shekinah: The Image of the Divine Feminine

The Feminine Spirit: Recapturing the Heart of Scripture

Islam and the Divine Feminine

Tao: The Divine Feminine and the Universal Mother

The Tao as the Divine Mother: Embracing All Things

The Tao of Laozi and the Revelation of the Divine Feminine

Doorway of Mysterious Female ... Within Us All the While

The Eternal Tao and the Doorway of the Mysterious Female

Divine Feminine Remains the Esoteric Heartbeat of Islam

Holy Spirit of Christ Is a Feminine Spirit

Divine Feminine and Spirit: A Profound Analysis of Ruha

The Divine Feminine in Sufism

The Primordial Mother of Humanity: Tao Is Brahman

The Divine Feminine in Sahaja Yoga

Shekinah: She Who Dwells Within

Shekinah Theology and Christian Eschatology

Ricky Hoty, The Divine Mother

Centrality of the Divine Feminine in Sufism

A God Who Needed no Temple

Silence on (your) Self

The Literal Breath of Mother Earth

Prophecy of the 13 Grandmothers

Aurobindo: "If there is to be a future"

The Tao Te Ching and Lalita Sahasranama stand alone

New Millennium Religion Ushered by Divine Feminine

A Comprehensive Comparison of Religions and Gurus