![]()

The Gospel of Thomas addresses itself only to a subtle elite, those capable of knowing

"Wherein are we hastening? Few of the hidden sayings of Jesus suggest that the destination of most of us is a solitary entrance into the wedding chamber. Whatever gnosticism was, or is, it must clearly be an elitist phenomenon, an affair of intellects, or of mystical intellectuals. The Gospel of Thomas addresses itself only to a subtle elite, those capable of knowing, who then through knowing can come to see what Jesus insists is plainly visible before them, indeed all around them. This Jesus has not come to take away the sins of the world, or to atone for all humankind. As one who passes by, he urges his seekers to learn to be passersby, to cease hastening to the temporal death of business and busyness that the world miscalls life. It is the busy world of death-in-life that constitutes the whatness from which we are being freed by the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas. There is no haste in this Jesus, no apocalyptic intensity. He does not teach the end-time, but rather a transvaluation of time, in the here of our moment.”

"Whoever discovers the interpretation of these sayings ...”

A READING

by Harold Bloom

The popularity of the Gospel of Thomas among Americans is another indication that there is indeed"The American religion": creedless, Orphic, enthusiastic, protognostic, post-Christian. Unlike the canonical gospels, that of Judas Thomas the Twin spares us the crucifixion, makes the resurrection unnecessary, and does not present us with a God named Jesus. No dogmas could be founded upon this sequence (if it is a sequence) of apothegms. If you turn to the Gospel of Thomas, you encounter a Jesus who is unsponsored and free. No one could be burned or even scorned in the name of this Jesus, and no one has been hurt in any way, except perhaps for those bigots, high church or low, who may have glanced at so permanently surprising a work.

I take it that the first saying is not by Jesus but by his twin, who states the interpretive challenge and its prize: more life into a time without boundaries. That was and is the blessing: "The kingdom is inside you and it is outside you.”Marvin Meyer is wary when it comes to naming these hidden sayings as gnostic, but I will not hesitate in making this brief commentary into a gnostic sermon that takes the Gospel of Thomas for its text. What makes us free is the gnosis, and the hidden things set down by Thomas form a part of a gnosis available to every Christian, Jew, humanist, skeptic, whoever you are. The trouble of finding, and being found, is simply the trouble that clears ignorance away, to be replaced by the gnostic knowing in which we are known even as we know ourselves. The alternative is precisely what Emerson and Wallace Stevens meant by 'poverty': imaginative lack or need. To believe that anything whatsoever is so does not redress 'poverty' in this sense. Knowledge only is the remedy, and such knowledge must be knowledge of the self. The Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas calls us to knowledge and not to belief, for faith need not lead to wisdom; and this Jesus is a wisdom teacher, gnomic and wandering, rather than a proclaimer of finalities. You cannot be a minister of this gospel, nor found a church upon it. The Jesus who urges his followers to be passersby is a remarkably Whitmanian Jesus, and there is little in the Gospel of Thomas that would not have been accepted by Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman.

Seeing what is before you is the whole art of vision for Thomas's Jesus. Many of the hidden sayings are so purely antithetical that they can be interpreted only by our seeing what they severely decline to affirm. No scholar ever will define precisely what gnosticism was or is, but its negations are palpable. Nothing mediates the self for the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas. Everything we seek is already in our presence, and not outside our self. What is most remarkable in these sayings is the repeated insistence that everything is already open to you. You need but knock and enter. What is best and oldest in you will respond fully to what you allow yourself to see. The deepest teaching of this gnostic Jesus is never stated but always implied, implied in nearly every saying. There is light in you, and that light is no part of the created world. It is not Adamic. I know of only two convictions essential to gnosis: Creation and fall were one and the same event; and what is best in us was never created, so cannot fall. The American religion, gnosis of our Evening-Land, adds a third element if our freedom is to be complete. That ultimate spark of the pre-created light must be alone, or at least alone with Jesus. The living Jesus of the

Gospel of Thomas speaks to all the followers, but in the crucial thirteenth saying he speaks to Thomas alone, and those sec ret three sayings are never revealed to us. Here we must surmise, since those three solitary sayings are the hidden heart of the Gospel of Thomas.

Thomas has earned knowledge of the sayings (or words) by denying any similitude for Jesus. His twin is not like a righteous messenger or prophet, nor is he like a wise philosopher, or teacher of Greek wisdom. The sayings then would turn upon the nature of Jesus: what he is. He is so much of the light as to be the light, but not the light of heaven, or of the heaven above heaven. The identification must be with the stranger or alien God, not the God of Moses and of Adam, but the man-god of the abyss, prior to creation. Yet there is only one truth out of three, though quite enough to be stoned for, and then avenged by divine fire. The second saying must be the call of that stranger God to Thomas, and the third must be the response of Thomas, which is his realization that he already is in the place of rest, alone with his twin.

Scholars increasingly assert that certain sayings in the Gospel of Thomas are closer to the hypothetical"Q"document than are parallel passages in the synoptic gospels. They generally ascribe the gnostic overtones of the Gospel of Thomas to a redactor, perhaps a Syrian ascetic of the second century of the Common Era. I would advance a different hypothesis, though with little expectation that scholars would welcome it. Of the veritable text of the sayings of a historical Jesus, we have nothing. Presumably he spoke to his followers and other wayfarers in Aramaic, and except for a few phrases scattered through the gospels, none of his Aramaic sayings has survived. I have wondered for some time how this could be, and wondered even more that Christian scholars have never joined in my wonder. If you believed in the divinity of Jesus, would you not wish to have preserved the actual Aramaic sentences he spoke, since they were for you the words of God? But what was preserved were Greek translations of his sayings, rather than the Aramaic saying themselves. Were they lost, still to be found in a cave somewhere in Israel? Were they never written down in the first place, so that the Greek texts were based only upon memory? For some years now, I have asked these questions whenever I have met a New Testament scholar, and I have met only blankness. Yet surely this puzzle matters. Aramaic and Greek are very different languages, and the nuances of spirituality and of wisdom do not translate readily from one into the other. Any sayings of Jesus, open or hidden, need to be regarded in this context, which ought to teach us a certain suspicion of even the most normative judgment as to authenticity, whether those judgments rise from faith or from supposedly positive scholarship.

My skepticism is preamble to my hypothesis that the gnostic sayings that crowd the Gospel of Thomas indeed may come from Q, or from some ur-Q, which would mean that there were protognostic elements in the teachings of Jesus. The Gospel of Mark, in my reading, is far closer to the J-writer or Yahwist than are the other gospels, and while I hardly find any gnostic shadings in Mark or the Yahwist, I do find uncanny moments not reconcilable with official Christianity and Judaism. Moshe Idel, the great revisionist scholar of Kabbalah, persuades me that what seem gnostic elements in Kabbalah actually stem from an archaic Jewish religion, anything but normative, of which what we call gnosticism may be an echo or parody. Christian gnosticism also may be a belated version of some of the teachings of Jesus. All of gnosticism, according to the late Ioan Couliano, is a kind of creative misinterpretation or strong misreading or misprision both of Plato and the Bible. Sometimes, as I contemplate organized institutional Christianity, historical or contemporary, it seems to me a very weak misreading of the teachings of Jesus. The Gospel of Thomas speaks to me, and to many others, Gentile and Jewish, in ways that Mark, Luke, and John certainly do not.

This excursus returns me to my professedly gnostic sermon upon the text of the Gospel of Thomas. How do the secret sayings of Jesus help to make us free? What knowledge do they give us of who we were, of what we have become, of where we were, of wherein we have been thrown, of whereto we are hastening, of what we are being freed, of what birth really is, of what rebirth really is? A wayfaring Jesus, as presented in Burton Mack's A Myth of Innocence, is accepted by Marvin Meyer as his vision of Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas, an acceptance in which I am happy to share. Mack rightly emphasizes that every text we have of Jesus is late; I would go a touch further and call them anxiously"belated.”Indeed, I return to my earlier question about our lack of the Aramaic text of what Jesus said: Is it not an extraordinary scandal that all the crucial texts of Christianity are so surprisingly belated? The Gospel of Mark is at least forty years later than the passion that supposedly it records, and the hypothetical Q depends upon collating material from Mathew and Luke, perhaps seventy years after the event. Mack's honest and sensible conclusion is to postulate a Jesus whose career does not center upon crucifixion and resurrection, but upon the wanderings of a kind of Cynic sage. Such a sage, in my own reading of the Gospel of Thomas, may well have found his way back to an earlier version of the Jewish religion than any we now recognize. And that earliness, as Idel has shown, anticipated much of what we now call gnosticism.

What begins to make us free is the gnosis of who we were, when we were"In the light.”When we were in the light, then we stood at the beginning, immovable, fully human, and so also divine. To know who we were, is to be known as we now wish to be known. We came into being before coming into being; we already were, and so never were created. And yet what we have become altogether belies that origin that was already an end. The Jesus of the Gospel of Jesus refrains from saying precisely how dark we have become, but subtly he indicates perpetually what we now are. We dwell in poverty, and we are that poverty, for our imaginative need has become greater than our imaginations can fulfill. The emphasis of this Jesus is upon a pervasive opacity that prevents us from seeing anything that really matters. Ignorance is the blocking agent that thwarts the every-early Jesus, and his implied interpretation of our ignorance is: belatedness. The hidden refrain of these secret or dark sayings is that we are blinded by an overwhelming sense that we have come after the event, indeed, after ourselves. What the gnostic Jesus warns against is retroactive meaningfulness, repetitive and incessant aftering. He has not come to praise famous men, and our fathers who were before us. Of men, he commends only John the Baptist and his own brother, James the Righteous. The normative nostalgia for the virtues of the fathers is totally absent. Present all around us and yet evading us are the intimations of the light, unseen except by Jesus.

An admonition against retroactive meaningfulness is neither Platonic nor normatively Jewish, and perhaps hints again at an archaic Jewish spirituality, of which apparent Gnosticism may be the shadow. The gnostic hatred of time is implicit in the Gospel of Thomas. Is it only a vengeful misprision both of Plato and the Hebrew Bible, or does it again hint at an archaic immediacy that Jesus, as wandering teacher, seeks to revive? Moshe Idel finds in some of the most ancient extra-biblical texts the image we associate now with Hermeticism and Kabbalah, the primordial Human, whom the angels resented and envied. To pass from that Anthropos to Adam is to fall into time, by a fall that is only the creation of Adam and his world. Certainly the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas has no fondness for Adam, who"came from great power and great wealth, but he is not worthy of you.”

Where were we, then, before we were Adam? In a place before creation, but not a world elsewhere. The kingdom, which we do not see, nevertheless is spread out upon the earth. Normative Judaism, from its inception, spoke of hallowing the commonplace, but the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas beholds nothing that is commonplace. Since the kingdom is inside us and outside us, what is required is that we bring the axis of vision and the axis of things together again. The stones themselves will then serve us, transparent to our awakened vision. Though the Gospel of Thomas avoids using the gnostic terms for the fullness, the Pleroma, and the cosmological emptiness, the Kenoma, their equivalent hover in the discourse of the wandering teacher of open vision. The living Jesus, never the man who was crucified nor the god who was resurrected, is himself the fullness of where once we were. And that surely is one of the effects of the Gospel of Thomas, which is to undo the Jesus of the New Testament and return us to an earlier Jesus. Burton Mack's central argument seems to me unassailable: 'The Jesus of the churches is founded upon the literary character, Jesus, as composed by Mark. I find this parallel to my argument, in The Book of J, that the Western worship of God—Judaic, Christian, Islam—is the worship not only of a literary character, but of the wrong literary character, the God of Ezra the Redactor rather than the uncanny Yahweh of the J writer. If the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas is also to be regarded as a literary character, then at least he too will be the right literary character, like the Davidic-Solomonic Yahweh.

Wherein, according to Thomas's Jesus, have we been thrown? Into the body, the world, and our temporal span in this world, or in the sum: Have we been thrown into everything that is not ourselves? I would not interpret this as a call to ascetic renunciation, since other sayings in the Gospel of Thomas reject fasting, almsgiving, and all particular diets. And though the Jesus of Thomas is hardly a libertine gnostic, his call to end both maleness and femaleness does not read to me as an evasion of all sexuality. We are not told what will make the two into one, and we should not interpret this conversion into one composite gender as something beyond the absorption of the female into the male. Everything here turns upon the image of the entrance of the bridegroom into the wedding chamber, which can be accomplished only by those who are solitaries, elitist individuals who in some sense have transcended gender distinctions. But this solitude need not be an ascetic condition, and it repeats or rejoins the figure of the pre-Adamic Anthropos, the human before the fall-into-creation. That figure, whether in ancient Jewish speculation (as Idel shows), or in Gnosticism, or in Kabbalah, is hardly removed from sexual experience.

Wherein are we hastening? Few of the hidden sayings of Jesus suggest that the destination of most of us is a solitary entrance into the wedding chamber. Whatever gnosticism was, or is, it must clearly be an elitist phenomenon, an affair of intellects, or of mystical intellectuals. The Gospel of Thomas addresses itself only to a subtle elite, those capable of knowing, who then through knowing can come to see what Jesus insists is plainly visible before them, indeed all around them. This Jesus has not come to take away the sins of the world, or to atone for all humankind. As one who passes by, he urges his seekers to learn to be passersby, to cease hastening to the temporal death of business and busyness that the world miscalls life. It is the busy world of death-in-life that constitutes the whatness from which we are being freed by the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas. There is no haste in this Jesus, no apocalyptic intensity. He does not teach the end-time, but rather a transvaluation of time, in the here of our moment.

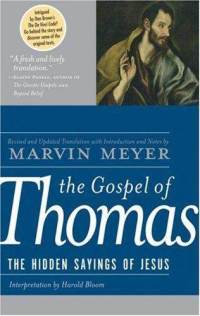

The Gospel of Thomas: The Hidden Sayings of Jesus

Marvin Meyer, HarperOne; 2nd edition (October 9, 1992) pp. 125-32

"But the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas is not interested in coercion, nor can anyone coerce in his name. The innocence of gnosticism is its freedom from violence and fraud, from which historical Christianity cannot be disentangled. No one is going to establish a gnostic church in America, by which I mean a professedly gnostic church, to which tax exemption would never be granted anyway. Of course we have gnostic churches in plenty: the Mormons, the Sothern Baptists, the Assemblies of God, Christian Science, and most other indigenous American denominations and sects. These varieties of the American religion, as I call it, are all involuntary parodies of the gnosis of the Gospel of Thomas. But ancient Gnosticism is neither to be praised nor blamed for its modern analogues. What is surely peculiar is the modern habit of employing 'gnosis' or 'gnosticism' as a conservative or institutionalized Christian term of abuse. An elitist religion, Gnosticism almost always has been a severely intellectual phenomenon, and the Jesus of the Gospel of Thomas is certainly the most intellectualized figure among all the versions of Jesus through the ages.”

The Gospel of Thomas: The Hidden Sayings of Jesus

Marvin Meyer, HarperOne; 2nd edition (October 9, 1992) pp. 134

Disclaimer: Our material may be copied, printed and distributed by referring to this site. This site also contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the education and research provisions of "fair use" in an effort to advance freedom of inquiry for a better understanding of religious, spiritual and inter-faith issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.