The Divine Feminine in China

This article explores the Divine Feminine in Chinese culture, tracing her presence from ancient shamanic traditions to Taoist philosophy and mythology. Revered as the Primordial Mother, she appears as Hsi Wang Mu—the Queen Mother of the West—and Kuan Yin, the goddess of compassion. Through sacred landscapes, poetic wisdom, and the Taoist principle of Wu Wei, the feminine is honored as the source of life, balance, and intuitive knowing. Her resonance with global archetypes like Isis, Devi, and Mary affirms her universal role as the Protectress of Life and embodiment of mercy, love, and wisdom.

Mother of all Creation

Once, in China, as elsewhere, there was a Mother who was before heaven and earth came into being. Her image was woven into the age-old beliefs of the people and the shamanic tradition which later evolved into Taoism. In Chinese mythology, the mother goddess has many names and titles. One legend imagined her as an immense peach tree which grew in the Garden of Paradise in the Kun-Lun mountains of the West and was the support of the whole universe. The fruit of this marvellous and magical tree ripened only after three thousand years, bestowing immortality on whoever tasted it. The Garden of Paradise belonged to the Queen of the Immortals, the Royal Mother of the West, whose name was Hsi Wang Mu, goddess of eternal life. Other myths describe her as the Mother or Grandmother, the primordial Heavenly Being, the cosmic womb of all life, the gateway of heaven and earth. Taoism developed on this foundation.

More subtly and comprehensively than any other religious tradition, Taoism (Daoism) nurtured the quintessence of the Divine Feminine, keeping alive the feeling of relationship with the ground of being as Primordial Mother. Somehow the Taoist sages discovered how to develop the mind without losing touch with the soul, and this is why an understanding of their philosophy - China's priceless legacy to humanity - is so important to us now.

The Origins of Taoism

The origins of Taoism come from the shamanic practices and oral traditions of the Bronze Age and beyond. Its earliest written expression is the Book of Changes or I Ching, a book of divination consisting of sixty-four oracles which is thought to date to 3000-1200 BC. The complementary images of yin and yang woven into the sixty-four hexagrams of the I Ching are not to be understood as two separate expressions of the one indivisible life energy: earth and heaven, feminine and masculine, female and male, for each contains elements of the other and each cannot exist without the other. In their passionate embrace, there is relationship, dialogue, and continual movement and change. The I Ching describes the flow of energies of the Tao in relation to a particular time, place, or situation and helps the individual to balance the energies of yin and yang and to listen to the deeper resonance of the One that is both.

The Tao Te Ching

The elusive essence of Taoism is expressed in the Tao Te Ching, the only work of the great sage Lao Tzu (born c. 604 BC), whom legend says was persuaded to write down the eighty-one sayings by one of his disciples when, reaching the end of his life, he had embarked on his last journey to the mountains of the West. The word Tao means the fathomless Source, the One, the Deep. Te is the way the Tao comes into being, growing organically like a plant from the deep ground or source of life, from within outwards. Ching is the slow, patient shaping of that growth through the activity of a creative intelligence that is expressed as the organic patterning of all instinctual life, like the DNA of the universe. "The Tao does nothing, yet nothing is left undone." The tradition of Taoism was transmitted from master to pupil by a succession of shaman-sages, many of whom were sublime artists and poets. In the midst of the turmoil of the dynastic struggles that engulfed China for centuries, they followed the Tao, bringing together the outer world of appearances with the inner one of Being.

The Way of Tao

From the source which is both everything and nothing, and whose image is the circle, came heaven and earth, yin and yang, the two principles whose dynamic relationship brings into being the world we see. The Tao is both the source and the creative process of life that flows from it, imagined as a Mother who is the root of heaven and earth, beyond all yet within all, giving birth to all, containing all, nurturing all. The Way of Tao is to reconnect with the mother source or ground, to be in it, like a bird in the air or a fish in the sea, in touch with it, while living in the midst of what the Taoists called the "sons" or "children" - the myriad forms that the source takes in manifestation. It is to become aware of the presence of the Tao in everything, to discover its rhythm and its dance, to learn to trust it, no longer interfering with the flow of life by manipulating, directing, resisting, controlling. It is to develop the intuitive awareness of a mystery which only gradually unveils itself. Following the Way of Tao requires a turning towards the hidden withinness of things, a receptivity to instinctive feeling, enough time to reflect on what is inconceivable and indescribable, beyond the reach of mind or intellect, that can only be felt, intuited, experienced at ever deeper depth. Action taken from this position of balance and freedom will gradually become aligned to the harmony of the Tao and will therefore embody its mysterious power and wisdom.

Wu Wei: The Art of Not-Doing

The Taoists never separated nature from spirit, consciously preserving the instinctive knowledge that life is One. No people observed nature more passionately and minutely than the Chinese sages or reached so deeply into the hidden heart of life, describing the life and form of insects, animals, birds, flowers, trees, wind, water, planets, and stars. They felt the continuous flow and flux of life as an underlying energy that was without beginning or end, that was, like water, never static, never still, never fixed in separate things or events, but always in a state of movement, a state of changing and becoming. They called the art of going with the flow of this energy Wu Wei, not-doing (Wu means not or non-, Wei means doing, making, striving after goals), understanding it as relinquishing control, not trying to force or manipulate life but attuning oneself to the underlying rhythm and ever-changing modes of its being. The stilling of the surface mind that is preoccupied with the ten thousand things brings into being a deeper, more complete mind and an integrated state of consciousness or creative power that they named Te, which enabled them not to interfere with life but to "enter the forest without moving the grass; to enter the water without raising a ripple."

Taoist Art and Poetry

They cherished the Tao with their brushstrokes, observing how it flowed into the patterns of cloud and mist between earth and mountain peak, or the rhythms of air currents and the eddying water of rivers and streams, the opening of plum blossom in spring, the graceful dance of bamboo and willow. They listened to the sounds that can only be heard in the silence. They expressed their experience of the Tao in their paintings, their poetry, the creation of their temples and gardens, and in their way of living, which was essentially one of withdrawal from the world to a place where they could live a simple, contemplative life, concentrating on perfecting their brushstrokes in calligraphy and painting and their subtlety of expression in the art of poetry. Humility, reverence, patience, insight, and wisdom were the qualities that they sought to cultivate.

The Primordial Mother in Chinese Culture

The image of the primordial Mother was embedded deep within the soul of the Chinese people who, as in Egypt, Sumer, and India, turned to her for help and support in time of need. She was particularly close to women who prayed to her for the blessing of children, for a safe delivery in childbirth, for the protection of their families, for the healing of sickness. Their mother goddess was not a remote being but a compassionate, accessible presence in their homes, in the sacred mountains where they went on pilgrimages to her temples and shrines, and in the valleys and vast forests where she could be felt, and sometimes seen. Yet, like the goddesses in other early cultures, she also had cosmic dimensions. Guardian of the waters, helper of the souls of the dead in their passage to other realms, she was the Great Mother who responded to the cry of all people who called upon her in distress. She was the Spirit of Life itself, deeper than all knowing, caring for suffering humanity, her child. Above all, she was the embodiment of mercy, love, compassion, and wisdom, the Protectress of Life. Although she had many names and images in earlier times, these eventually merged into one goddess who was called Kuan Yin - She who hears, She who listens.

Kuan Yin: The Compassionate Goddess

By a fascinating process which saw the blending of different religious traditions, the ancient Chinese Mother Goddess absorbed elements of the Buddhist image of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, the Tibetan mother goddess Tara, and the Virgin Mary of Christianity, whose statues were brought to China during the seventh century AD. The name Kuan Yin was a translation of the Sanskrit word Avalokitesvara and means "The One Who Hears the Cries of the World." At first, following the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, this compassionate being was imagined in male form, but from the fifth century AD, the female form of Kuan Yin begins to appear in China, and by the tenth century, it predominates.

It was in the far north-west, at the interface between Chinese, Tibetan, and European civilizations, that the cult of Kuan Yin took strongest root, and it was from here that it spread over the length and breadth of China and into Korea and Japan, grafted onto the far older image of the Mother Goddess. Every province had its local image and its own story about her. Taoist and Buddhist elements were fused, creating an image of the Divine Feminine that was deeply satisfying to the people. By the 16th century, Kuan Yin had become the principal deity of China and Japan and is so today. Robed in white, she is usually shown seated or standing on a lotus throne, sometimes with a child on her lap or near her, for she brings the blessing of children to women.

Descriptions of Kuan Yin

Chinese Buddhist texts describe her as being within a vast circle of light that emanates from her body, her face gleaming golden, surrounded with a garland of 8000 rays. The palms of her hands radiate the colour of 500 lotus flowers. The tip of each finger has 84,000 images, each emitting 84,000 rays whose gentle radiance touches all things. All beings are drawn to her and compassionately embraced by her. Meditation on this image is said to free them from the endless cycle of birth and death.

Listen to the deeds of Kuan Yin

Responding compassionately on every side

With great vows, deep as the ocean,

Through inconceivable periods of time,

Serving innumerable Buddhas,

Giving great, clear, and pure vows...

To hear her name, to see her body,

To hold her in the heart, is not in vain,

For she can extinguish the suffering of existence...

The Divine FeminineHer knowledge fills out the four virtues,

Her wisdom suffuses her golden body.

Her necklace is hung with pearls and precious jade,

Her bracelet is composed of jewels.

Her hair is like dark clouds wondrously arranged like curling dragons;

Her embroidered girdle sways like a phoenix's wing in flight.

Sea-green jade buttons,

A gown of pure silk,

Awash with Heavenly light;

Eyebrows as if crescent moons,

Eyes like stars.

A radiant jade face of divine joyfulness,

Scarlet lips, a splash of colour.

Her bottle of heavenly dew overflows,

Her willow twig rises from it in full flower.

She delivers from all the eight terrors,

Saves all living beings,

For boundless is her compassion.

She resides on T'i Shan,

She dwells in the Southern Ocean.

She saves all the suffering when their cries reach her,

She never fails to answer their prayers,

Eternally divine and wonderful.

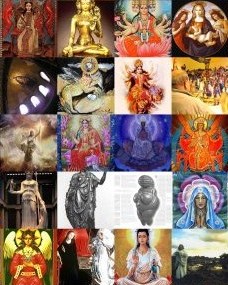

Exploring the Feminine Face of God throughout the World

Godsfield Press UK and Conari Press USA 1996

Anne Baring and Andrew Harvey

The Divine Feminine in Chinese Culture and Beyond

The Divine Feminine in Chinese culture, as embodied by figures like Hsi Wang Mu and Kuan Yin, resonates profoundly with similar archetypes found in other ancient civilizations. This universal archetype of the Great Mother transcends cultural and geographical boundaries, reflecting a shared human understanding of creation, nurturing, and compassion. Below is an analysis of how the Divine Feminine of China aligns with that of other cultures, emphasizing the unity of this archetype across civilizations.

1. The Primordial Mother Archetype

- China: In Chinese mythology, the primordial Mother is the source of all creation, often depicted as the cosmic womb or the support of the universe. Hsi Wang Mu, the Queen of the Immortals, embodies eternal life and cosmic power.

- Egypt: The Egyptian goddess Isis is revered as the Mother of All, the giver of life, and the protector of the dead. She is often depicted nursing her son Horus, symbolizing nurturing and rebirth.

- Sumer: The Sumerian goddess Inanna (or Ishtar) represents fertility, love, and the cycles of life and death.

- India: The Hindu goddess Devi (or Shakti) is the primordial energy of the universe, worshipped in many forms such as Durga (protector) and Kali (destroyer of evil).

Unity: Across these cultures, the Divine Feminine is seen as the source of life, the sustainer of the universe, and the force of regeneration.

2. The Compassionate Mother

- China: Kuan Yin, the goddess of mercy, is revered for her ability to hear the cries of the suffering and offer solace.

- Christianity: The Virgin Mary is venerated as the Mother of God, embodying purity, compassion, and intercession.

- Tibetan Buddhism: The goddess Tara is a compassionate savior who aids beings in distress.

- Greek Mythology: Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, ensures the growth of crops and the well-being of humanity.

Unity: The compassionate aspect of the Divine Feminine represents unconditional love and mercy.

3. The Cosmic and Earthly Duality

- China: The Divine Feminine in Taoism is both cosmic (the source of heaven and earth) and earthly (present in nature and daily life).

- Mesopotamia: The goddess Tiamat represents the primordial chaos and the cosmic waters from which creation emerges.

- Greek Mythology: Gaia, the Earth Mother, is both the physical earth and the cosmic force that sustains it.

- Native American Traditions: The Corn Mother or Earth Mother embodies the cycles of nature.

Unity: The Divine Feminine is both transcendent and immanent, existing as the cosmic source of life and the nurturing force of nature.

4. The Healer and Protector

- China: Kuan Yin is a healer who brings blessings of children, safe childbirth, and protection.

- Egypt: Isis is a healer who restores life and protects the dead.

- Celtic Traditions: The goddess Brigid is associated with healing and poetry.

- African Traditions: The Yoruba goddess Yemoja is associated with water, fertility, and healing.

Unity: The Divine Feminine is a healer and protector, offering solace and guidance in times of need.

5. The Syncretic Evolution of the Divine Feminine

- China: Kuan Yin blends Buddhist, Taoist, and Christian influences.

- Egypt: Isis absorbed attributes of other goddesses and became a universal deity.

- India: Devi encompasses countless forms and functions.

- Greece: Aphrodite merged with Venus and Ishtar.

Unity: The Divine Feminine evolves, absorbing attributes from different cultures and reflecting universal spiritual needs.

6. The Divine Feminine as a Unifying Force

Across cultures, the Divine Feminine represents the interconnectedness of all life. Whether as Kuan Yin, Isis, Devi, or Mary, she is a universal archetype that transcends time and geography.

Conclusion

The Divine Feminine of China, as embodied by Hsi Wang Mu and Kuan Yin, is part of a global tapestry of goddess archetypes that share common themes of creation, compassion, healing, and protection. Her resonance with figures like Isis, Devi, Mary, and Tara underscores the universality of this archetype. She is not merely a cultural construct but a profound expression of the human experience, reflecting our deepest values and aspirations. The Divine Feminine is a timeless, unifying force that embodies the essence of life itself.

Pariah Kutta (https://adishakti.org)OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT

Related Articles:

The Divine Feminine in Biblical Wisdom Literature

The Divine Mother by Ricky Hoyt

The Divine Feminine In China

The Feminine Spirit: Recapturing The Heart Of Scripture

The Divine Feminine: The Great Mother

Islam and the Divine Feminine

Tao: The Divine Feminine and the Universal Mother

The Tao as the Divine Mother: Embracing All Things

The Tao of Laozi and the Revelation of the Divine Feminine

"Doorway of Mysterious Female ... within us all the while."

The Eternal Tao and the Doorway of the Mysterious Female

The Divine Feminine remains the esoteric heartbeat of Islam

Holy Spirit of Christ is a feminine Spirit

Divine Feminine and Spirit: A Profound Analysis of Ruha

The Divine Feminine in Sufism

The Primordial Mother of Humanity

Centrality of Divine Feminine in Sufism