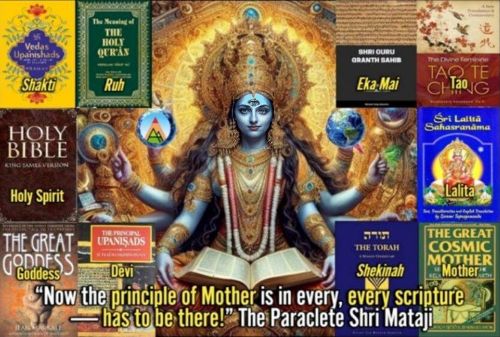

DIVINE FEMININE: The Great Mother

This article traces the sacred legacy of the Great Mother, the primordial Divine Feminine revered across cultures and epochs. From Paleolithic goddess figurines to Neolithic rituals and Bronze Age hymns, She emerges as the source of life, cosmic order, and spiritual regeneration. Her presence is felt in the rhythms of nature, the cycles of birth and death, and the mystical connection between humanity and the cosmos. Through sacred texts like the Devi Gita, Rig Veda, Puranas, Lalita Sahasranama, and Tao Te Ching, the Great Mother speaks as the eternal consciousness permeating all existence. She is the tree of life, the cave of being, and the soul of the world—awakening us to our divine origins and our sacred future.

“Human consciousness has developed infinitely slowly out of nature. Before we knew ourselves as human, we were animal and plant, stone and water. For countless millennia, the potential for human consciousness was hidden within nature, like a seed buried in the earth. Then, very slowly, it began to differentiate itself from nature. Deep in our memory is the whole experience of life on this planet: life that has evolved over the four and a half billion years since its formation; life as hydrogen, oxygen and carbon; life as the most minute particles of matter; life as water, fire, air and earth; life as rock, soil, plant, insect, bird, animal; life as woman and man evolved from this aeonic experience. Finally the point was reached where planetary life evolved a brain which enabled us to speak, to formulate thoughts, to communicate with each other through language, to endow sounds with meaning, and invent writing as a way of transmitting thoughts. Over these billions of years life on this planet has evolved from undifferentiated awareness to the self-awareness of our species. All this can be described as an instinctive process, each phase blending imperceptibly into the next.

Self-awareness and reflective consciousness as we know it now is a very recent development, yet consciousness as genetic patterning present in plant and animal and human life, consciousness as awareness or instinctive reflex is carried within us as part of the reptilian and mammalian brain system that took many millions of years to evolve. From these have come the highly differentiated consciousness of the neo-cortex that we call rational mind. The ability to think, to reason, to reflect, to analyse, to store information and be able to retrieve it through memory, is itself a development of the older brain systems, and is interdependent with them, but our conscious awareness is focused in the most recently developed part of ourselves and is out of touch with the roots from which we have grown. And what are those roots? Does our consciousness originate in the greater consciousness of the cosmos? Is our brain a vehicle, just as all planetary life is a vehicle, of that cosmic consciousness? Is the cosmos the ultimate source of our thoughts, our feelings, our fertile imagination, our creative ideas, our musical genius? These are questions to which science as yet gives no answer but older traditions from ancient civilizations do offer answers.

As consciousness evolved, the sacred image was like an umbilical cord connecting us to the deep ground of life. From about 25,000 BC., perhaps far longer, the image of the goddess as the Great Mother was worshipped as the fertile womb which gave birth to everything, the great cave of being from which she brought forth the living and into which she took the dead back for rebirth. To this day, the cave is still, in dream and mystical experience, the place of revelation and communion with the unseen ground of being. The earliest images of the Great Mother known to us are the figures of the goddess carved from stone and bone and ivory some 22,000 years ago. The Great Mother was imagined to carry within her being the three dimensions of sky, earth and underworld. She was the great pulse of life reflected in the rhythm of the moon, the sun, the stars, the plants, trees, animals and human beings. All these were her children and she was the numinous presence within her manifest forms, continually regenerating them in a cyclical process that was without beginning and without end.

This primordial experience of the Great Mother is the foundation of later cultures all over the world. She is like an immense tree, whose roots lie beyond the reach of our consciousness, whose branches are all the forms of life we know, and whose flowering is a potential within us, a potential that only a tiny handful of the human race has realized. In these earliest Paleolithic cultures of which those of the First Peoples today are the descendents, she was nature, she was the earth and she was the unseen dimension of soul or spirit. People were connected through her to nature as to a great being and to the great vault of the starry sky as part of this being, imagined as a great web of life. She was experienced as a law, a profound patterning which the whole of life reflected and obeyed in the way it functioned, from the circumpolar movement of the stars to the tiniest insect. The image of the Great Mother reflected something deeply felt - that the creative source cares for the life it has brought into being in the way that an animal or a human mother instinctively cares for the life of her cub or her child.

In the Neolithic, a deep relationship was formed with the earth through the rituals of sowing, tending and harvesting the crops, and breeding domestic animals for food. The images of the Great Mother as a profoundly experienced life process of birth, death and regeneration develop and proliferate around many different images of the goddess. Sky, earth, and underworld were unified in her being. As bird-goddess she was the sky and her life-bestowing waters fell as the rain from her breasts, the clouds; she was the earth and from her body were born the crops that nourished the life she supported. As serpent-goddess she was the darkness beneath the earth - the mysterious underworld - which concealed the hidden sources of the water which became the rivers, springs and lakes and which was also the home of the ancestral dead. She was the sea on which the fragile boats of the Neolithic explorers ventured into the unknown. She was the life of the animals, trees, plants and fruits on which all her children depended for survival. Whether we look at the goddess figures of Old Europe or those of atal Huyuk in Anatolia, or further East, to Mesopotamia and the Indus valley civilization, the basic forms are the same. It is hard for our modern consciousness to imagine how life in that time was lived in the dimension of the Mother, in participation with the rhythms of her being, or how these images of her kept people in touch with their instincts, and were the foundation of their fragile trust in life.

This was the phase in human evolution when magical rituals were devised to keep the community in harmony with her deeper life: to propitiate her with offerings that would bring protection and increase, and ward off her power to destroy. In relation to human consciousness at that time, the image of the Great Mother was numinous and all-powerful. The discoveries in the territory of Old Europe and at atal Huyuk in Anatolia and the Indus Valley show cultures as early as 7000 BC. with a deep sense of relationship with The Mother goddess, where women were engaged in all kinds of creative work that was focused on her worship, where shrines and temples to her abounded, filled with the beautiful pottery, cloth hangings and sculptures and the baked offerings that were made in her honor. It was in the Neolithic that mountains, hills and groves became sacred and that springs and wells became places of healing. There are still places all over the world where pilgrimages are made to these sacred sites. Deep in the psyche we carry ancient memories of the sacredness of the earth, and of the earth as Mother. This Neolithic vision was transmitted to the poetry and traditions of the First Peoples who are helping us now to recover our lost sense of the sacredness of the earth.

The Paleolithic and Neolithic eras give us the earliest images of the Great Mother but we hear no words. It is only in the Bronze Age that we begin to hear the human voice; for the first time we can listen to the hymns addressed to the great goddesses of Sumer and Egypt. The voice of the Divine Feminine comes alive, speaks to us, reflected in the words addressed to the goddess which are inscribed in hieroglyphs on the walls of Egyptian temples or on the sun-baked clay tablets of Sumer. These reveal a rich mythology of the Divine Feminine which may already be millennia old. It is in the Bronze Age that the feeling for the sacredness of life is clearly expressed in words - a feeling that is transmitted through the hymns and prayers to the goddess or where she herself speaks in the great aretalogies that have come down to us from Egypt and Canaan and the remarkable early Christian Gnostic texts discovered at Nag Hammadi. In these she announces herself to be the source, ground or matrix of all forms of life; the fertile womb which eternally regenerates plants, animals, human beings; the life-force which attracts the male to the female; the power which creates, destroys and transforms all forms of itself. The goddess speaks as the source and embodiment of all instinctive processes. She is the life force which is nurturing, compassionate, beneficent and also the terrifying and implacable force of destruction which can nevertheless regenerate what it has destroyed.

With the Iron Age, which begins about 1200 B.C., and the development of patriarchal religion, the story of the goddess becomes more difficult to follow as the god takes her place as the supreme ruler of sky, earth and underworld, yet in the West, the great goddesses of the Bronze Age are still worshipped as late as Roman times and the Greek and Roman goddesses, as well as moving closer to the concerns of civilization in their patronage of human skills and the creative arts, still bring through the cosmic dimensions of the older Great Goddess. Now they embody wisdom, truth, compassion and justice. They reflect the divine harmony, order and beauty of life. Inanna, Isis, Cybele, Demeter were the focus of mystery religions which gave access in the cultures over which they presided to a deeper perception of life than that which prevailed in the popular religions of the day. The magnificent lunar myth of Inanna's descent to and return from the underworld may be the foundation of the later image of the Shekhinah that emerges in the mystical tradition of the Hebrew religion. Through the celebration of the great festival in honor of Demeter, the Thesmophoria, and the rites of her temple at Eleusis, women and men were given a vision of eternal life and the mysteries of the soul.

The legacy of the Divine Feminine in Western culture lies in the great mythological themes of the Quest which direct us toward the roots of consciousness, the source or ground of being: the goddess Isis gathering the dismembered fragments of her husband, Osiris; Odysseus returning home to Penelope under the guidance of the goddess Athena; Theseus following Ariadne's thread through the Cretan labyrinth; Dante's journey into the underworld and his reunion with Beatrice; the medieval quest for the Holy Grail—all these marvellous stories define the Feminine as immanent presence and transcendent goal.

Further to the East, in India, while the Vedic sages expressed with extraordinary clarity their vision of the divine ground in the sublime poetic imagery of the Vedas and the Upanishads, the ecstatic poets whose traditions belonged to a culture which existed long before the Aryan invasions, sang of their passionate devotion to the goddess, while to the north, the mountain people named their great mountains in her honor and worshipped her as the dynamism of the creative principle, locked in the bliss of an eternal embrace with her divine consort.

Still further to the East, the wise masters of the Taoist tradition never lost the shamanic understanding that relationship with Nature was the key to staying in touch with the source of life. They never followed the ascetic practices of other religions which sacrificed the body for the sake of spiritual advancement. They were never in a hurry to reach the goal of union with the divine or to renounce the world for the sake of enlightenment. Of all the religious traditions, with the exception of those of the First Peoples, they were the only ones not to split body from spirit, thinking from feeling, so losing touch with the soul. They never became lost in the mazes of the intellect and its rigid metaphysical constructions but, through patience and devotion, were able to realize the difficult alchemy of bringing their nature into harmony with the deeper harmony of life. They did not lose sight of the One.”

Central Theological and Philosophical Characteristics

“An underlying theological assumption in texts celebrating the Mahadevi is that the ultimate reality in the universe is a powerful, creative, active, transcendent female being. The Lalita-sahasranama gives many names of the Mahadevi, and several of her epithets express this assumption. She is called, for example, the root of the world (Jagatikanda, name 325), she who transcends the universe (Visvadhika, 334), she who has no equal (Nirupama, 389), supreme ruler (Paramesvari, 396), she who pervades all (Vyapini, 400), she who is immeasurable (Aprameya, 413), she who creates innumerable universes (Anekakotibrahmandajanani, 620), she whose womb contains the universe (Visvagarbha, 637), she who is the support of all (Sarvadhara, 659), she who is omnipresent (Sarvaga, 702), she who is the ruler of all worlds (Sarvalokesi, 758), and she who supports the universe (Visvadharini, 759). In the Devi-bhagavata-purana, which also assumes the ultimate priority of the Mahadevi, she is said to be The Mother of all, to pervade the three worlds, to be the support of all (1.5.47-50), to be the life force of all beings, to be the ruler of all beings (1.5.51-54), to be the only cause of the universe (1.7.27), to create Brahma, Visnu, and Siva and to command them to perform their cosmic tasks (3.5.4.), to be the root of the tree of the universe (3.10.15), and to be she who is supreme knowledge (4.15.12). The text describes her by many other names and phrases as it exalts her to a position of cosmic supremacy.

The Concept of Sakti

One of the central philosophic ideas underlying the Mahadevi, an idea that in many ways captures her essential nature, is sakti. Sakti means "power"; in Hindu philosophy and theology sakti is understood to be the active dimension of the godhead, the divine power that underlies the godhead's ability to create the world and to display itself. Within the totality of the godhead, sakti is the complementary pole of the divine tendency towards quiescence and stillness. It is quite common, furthermore, to identify sakti with a female being, a goddess, and to identify the other pole with her male consort. The two poles are understood to be interdependent and to have relatively equal status in terms of divine economy.

Texts of contexts exalting the Mahadevi, however, usually affirm sakti to be a power, or the power, underlying ultimate reality, or to be the ultimate reality itself. Instead of being understood as one or two poles or as one dimension of a bipolar conception of the divine, sakti as it applies to the Mahadevi is often identified with the essence of reality. If the Mahadevi as sakti is related to another dimension of the divine in the form of a male deity, he will tend to play a subservient role in relation to her. In focussing on the centrality of sakti as constituting the essence of the divine, texts usually describe the Mahadevi as a powerful, active, dynamic being who creates, pervades, governs, and protects the universe. As sakti, she is not aloof from the world but attentive to the cosmic rhythms and the needs of her devotees.

Identification with Prakrti and Maya

In a similar vein the Mahadevi is often identified with prakrti and maya. Indeed, two of her most common epithets are Mulaprakrti (she who is primordial matter) and Mahamaya (she who is great maya)... In the quest for liberation prakrti represents that from which one seeks freedom. Similarly, most schools of Hindu philosophy identify maya with that which prevents one from seeing things as they really are. Maya is the process of superimposition by which one projects one's own ignorance on the world and thus obscures ultimate truth. To wake up to the truth of things necessarily involves counteracting or overcoming maya, which is grounded in ignorance and self-infatuation. Liberation in Hindu philosophy means to a great extent the transcendence of embodied, finite, phenomenal existence. And maya is often equated precisely with finite, phenomenal existence. To be in the phenomenal world, to be an individual creature, is to live enveloped in maya.

When the Mahadevi is associated with prakrti or maya, certain negative overtones sometimes persist. As prakrti or maya she is sometimes referred to as the great power that preoccupies individuals with phenomenal existence or as the cosmic force that impels even the gods to unconsciousness and sleep. But the overall result of the Mahadevi's identification with prakrti and maya is to infuse both ideas with positive dimensions. As prakrti or maya, the Devi is identified with existence itself, or with that which underlies all existent things. The emphasis is not on the binding aspects of matter or the created world but on the Devi as the ground of all things. Because it is she who pervades the material world as prakrti or maya, the phenomenal world tends to take on positive qualities. Or perhaps we could say that a positive attitude toward the world, which is evident in much of popular Hinduism, is affirmed when the Devi is identified with prakrti and maya. The central theological point here is that the Mahadevi is the world, she is all this creation, she is one with her creatures and her creation. Although a person's spiritual destiny ultimately may involve transcendence of the creation, the Devi's identification with existence per se is clearly intended to be a positive philosophical assertion. She is life, and to the extent that life is cherished and revered, she is cherished and revered.

The Devi as Brahman

The idea of brahman is another central idea with which the Devi is associated. Ever since the time of the Upanishads, brahman has been the most commonly accepted term or designation for the ultimate reality in Hinduism. In the Upanishads, and throughout the Hindu tradition, brahman is described in two ways: as nirguna (having no qualities or beyond all qualities) and saguna (having qualities). As nirguna, which is usually affirmed to be the superior way of thinking about brahman, ultimate reality transcends all qualities, categories, and limitations. As nirguna, brahman transcends all attempts to circumscribe it. It is beyond all name and form (nama-rupa). As the ground of all things, as the fundamental principle of existence, however, brahman is also spoken of as having qualities, indeed, as manifesting itself in a multiplicity of deities, universes, and beings. As saguna, brahman reveals itself especially as the various deities of the Hindu pantheon. The main philosophical point asserted in the idea of saguna brahman is that underlying all the different gods is a unifying essence, namely, brahman. Each individual deity is understood to be a partial manifestation of brahman, which ultimately is beyond all specifying attributes, functions, and qualities.

The idea of brahman serves well the attempts in many texts devoted to the Devi to affirm her superior position in the Hindu pantheon. The idea of brahman makes two central philosophical points congenial to the theology of the Mahadevi: (1) she is ultimate reality itself, and (2) she is the source of all divine manifestations, male and female (but especially female). As saguna brahman, the Devi is portrayed as a great cosmic queen enthroned in the highest heaven, with a multitude of deities as the agents through which she governs the infinite universes. In her ultimate essence, however, some texts, despite their clear preference for the Devi's feminine characteristics, assert in traditional fashion that she is beyond all qualities, beyond male and female.”

University of California Press; 1 edition (July 19, 1988), Pages 133-37

The Holy Spirit: The Feminine Aspect of the Godhead

“There is currently much talk of "feminine issues," particularly in social and political contexts. This growing awareness of gender-related matters was not something ignored by the early Church and the writers of ancient religious texts. As we see in this article by Dr. Hurtak, the notion of femininity played an extremely important and significant role in the thinking and belief system of the intertestamental authors. Far from being the overbearing patriarchal advocates as they are often portrayed, more recent findings reveal an innate sensitivity and appreciation for the feminine aspect of Divinity than has been previously suspected. For this reason, this particular article becomes a meaningful and insightful contribution to the current discussion of the role of the female in modern times. Once more we find a rich and profound history reshaping the future even as it unfolds before our eyes.

The Holy Spirit in Judeo-Christian Traditions

A new response to the "Image" of the Holy Spirit is taking shape quietly in scholarly circles throughout the world, as the result of new findings in the Dead Sea Scriptures, the Coptic Nag Hammadi and intertestamental texts of Jewish mystics found side-by-side the writings of the early Christian church. Scholars are recognizing the Holy Spirit as the "female vehicle" for the outpouring of higher teaching and spiritual rebirth. The Holy Spirit plays varied roles in Judeo-Christian traditions: acting in Creation, imparting wisdom, and inspiring Old Testament prophets. In the New Testament She is the presence of God in the world and a power in the birth and life of Jesus.

The Holy Spirit became well-established as part of a circumincession, a partner in the Trinity with the Father and Son after doctrinal controversies of the late 4th century AD solidified the position of the Western Church. Although all Christian Churches accept the union of three persons in one Godhead, the Eastern Church, particularly the communities of the Greek, Ethiopian, Armenian, and Russian, do not solidify a strong union of personalities, but see the figures uniquely differentiated, but still in union. Moreover, the Eastern Church places the Holy Spirit as the Second Person of the Trinity with Christ as the Third, whereas the Western Church places the Son before the Holy Spirit. In the Old Testament and the Dead Sea Scrolls the Holy Spirit was known as the Ruach or Ruach Ha Kodesh (Psalm 51:11). In the New Testament as Pneuma (Romans 8:9). The Holy Spirit was not rendered as "Holy Ghost" until the appearance of the 1611 Protestant King James Version of the Bible. For the most part, Ruach or Pneuma have been considered the spiritual force or presence of God. The power of this force can be seen in the Christian church as the "gifts of the Spirit" (especially in today's tongues-speaking Pentecostals).The Holy Spirit was also a source for Divine guidance and as the indwelling Comforter.

The Feminine Nature of the Holy Spirit

Likewise in Hebrew thought, Ruach Ha Kodesh was considered a voice sent from on high to speak to the Prophet. Thus, in the Old Testament language of the prophets, She is the Divine Spirit of indwelling sanctification and creativity and is considered as having a feminine power. "He" as a reference to Spirit has been used in theology to match the pronoun for God, yet the Hebrew word ruach is a noun of feminine gender. Thus, referring to the Holy Spirit as "she" has some linguistic justification. Denoting Spirit as a feminine principle, the creative principle of life, makes sense when considering the Trinity aspect where Father plus Spirit leads to the Divine Extension of Divine Sonship.

The Spirit is not called "It" despite the fact that pneuma in Greek is a neuter noun. Church doctrine regards the Holy Spirit as a person, not a force like magnetism. The writings of the Catholic fathers, in fact, preserve the vision of the Spirit encapsulating the "peoplehood of Christ" as the Bride or as the "Mother Church." Both are feminine aspects of the Divine. In the Eastern Church, Spirit was always considered to have a feminine nature. She was the life-bearer of the faith. Clement of Alexandria states that "she" is an indwelling Bride. Amongst the Eastern Church communities there is none more clear about the feminine aspect of the Holy Spirit as the corpus of the Coptic-Gnostics. One such document records that Jesus says, "Even so did my mother, the Holy Spirit, take me by one of my hairs and carry me away to the great mountain Tabor [in Galilee]."

Early Christian Writings and the Holy Spirit

The 3rd century scroll of mystical Coptic Christianity, The Acts of Thomas, gives a graphic account of the Apostle Thomas' travels to India, and contains prayers invoking the Holy Spirit as "The Mother of all creation" and "compassionate mother," among other titles. The most profound Coptic Christian writings definitely link the "spirit of Spirit" manifested by Christ to all believers as the "Spirit of the Divine Mother." Most significant are the new manuscript discoveries of recent decades which have demonstrated that more early Christians than previously thought regarded the Holy Spirit as the Mother of Jesus.

One text is the Gospel of Thomas which is part of the newly discovered Nag Hammadi texts (discovered 1945-1947). Most are composed about the same time as the Biblical gospels in the 1st and 2nd century AD. In this gospel, Jesus declares that his disciples must hate their earthly parents (as in Luke 14:26) but love the Father and Mother as he does, "for my mother (gave me falsehood), but (my) true Mother gave me life." In another Nag Hammadi discovery, The Secret Book of James, Jesus refers to himself as "The son of the Holy Spirit." These two sayings do not identify the Holy Spirit as the mothering vehicle of Jesus, but more than one scholar has interpreted them to mean that the maternal Holy Spirit is intended.

Modern Theological Perspectives

So far in Western traditional theology, the voices advocating a feminine Holy Spirit are scattered and subtle. But for them, it is a view theologically defensible and accompanied by psychological, sociological, and scientific benefits of recognizing "The new supernature" developing within vast consciousness changes happening in the human evolution.

The German theologian Jurgen Moltmann, a well-known thinker in mainline Protestantism, says "monotheism is monarchism." He says a traditional idea of God's absolute power "generally provides the justification for earthly domination" — from the emperors and despots of history to 20th century dictators. Moltmann argues for a new appreciation of the "persons" of the Trinity and the community or family model it presents for human relations.

According to Professor Neil Q. Hamilton at Drew University School of Theology, the Gospel of John shows us how "The Holy Spirit begins to perform a mothering role for us that is unconditional acceptance, love and caring." God then begins to parent us in father and mother modes.

A Catholic scholar, Franz Mayr, a philosophy professor at the University of Portland, also favors the recognition of the Holy Spirit as feminine. He contends that the traditional unity of God would not have to be watered down in order for scholars to accept the feminine side of God. Mayr, who studied under the renowned German theologian Karl Rahner, said he came to his view during his study of the writings of St. Augustine (AD 354-430) who saw that a significant number of early Christians must have accepted a feminine aspect of the Holy Spirit such that the influential church father of North Africa castigated this view. St. Augustine claimed that the acceptance of the Holy Spirit as the "mother of the Son of God and wife-consort of the Father" was merely a pagan outlook. But Mayr contends that Augustine "skipped over the social and maternal aspect of God," which Mayr thinks is best seen in the Holy Spirit, the Divine Ruach Ha Kodesh. St. Jerome, a contemporary of Augustine's, and two church fathers of an earlier period, Clement of Alexandria and Origen, quoted from the pseudopigraphic Gospel of the Hebrews, which depicted the Holy Spirit as a "mother figure."

Historical Depictions and Future Implications

A 14th Century fresco in a small Catholic Church southeast of Munich, Germany depicts a female Spirit as part of the Holy Trinity, according to Leonard Swidler of Temple University. The woman and two bearded figures flanking her appear to be wrapped in a single cloak and joined in their lower halves showing a union of old and new bodies of birth and rebirth.

In conclusion, we are living at a time of profound and revelatory discoveries of archaeology and ancient spiritual texts that point the way to the future. Christ, himself, was said to have female disciples as disclosed in Gnostic literature and recent archeological findings of early Christian tombs in Italy. A beginning has been made to reclaim "The Spirit" of the Ruach found in the mountain of newly discovered pre-Christian texts and Coptic-Egyptian texts of the early Church. It is becoming clear in re-examining the first 100 years of Christianity that an earlier Christianity was closer to the "Feminine Spirit" of the Old Testament, the Ruach or the beloved Shekinah. The Shekinah, distinct from the Ruach, was seen as the indwelling Divine Presence that activated the "birth of miracles" or the anointed self. Accordingly, the growth of traditional Christianity made alternative adjustments of the original position of the "birth of gifts" as Christendom compromised for the privilege of becoming an establishment.

The new directions of spiritual and scientific studies are showing that it is now possible that the Holy Spirit, Ruach Ha Kodesh, can be portrayed as feminine as the indwelling presence of God, the Shekinah, nurturing and bringing to birth souls for the kingdom. Spiritual insights recorded in the Book of Knowledge: Keys of Enoch carefully remind us that we are being prepared to understand that just as the Old Testament was the Age of the Father, the New Testament the Age of the Son, so this coming Age where gifts are poured forth will be the Age of the Holy Spirit."

J. J. Hurtak, PhD, The Academy For Future Science

Catalog of Biblical and Sacred Scrolls

Office: P.O. Box 3080 Sedona, AZ 86340 USA

The Adi Shakti Tradition

A convergence of scriptural, mystical, and experiential traditions offering a contemporary framework for understanding divinity, spiritual evolution, and eschatology.

The Adi Shakti sources represent a unique convergence of scriptural, mystical, and experiential traditions, offering a contemporary framework through which the deepest mysteries of divinity, spiritual evolution, and eschatology can be understood and accessed. Rooted in centuries-old Eastern and Western religious texts—and brought to distinct prominence through the teachings of Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi—they illuminate a path that emphasizes the universality of the Divine Feminine, the transformative power of the Holy Spirit, and the promise of collective Self-realization. This extended introduction situates these sources within their historical, philosophical, and spiritual contexts, guiding the reader through the themes, lineage, and global impact of the Adi Shakti tradition.

Historical and Scriptural Origins

The Adi Shakti tradition draws from a profound tapestry of religious and philosophical literature across Hinduism, Christianity, and Judaism. "Adi Shakti," literally the "Primordial Power," is rooted in ancient Indian understandings of the feminine principle as the source of all creation, exemplified in figures such as MahaDevi and various goddesses throughout the Vedas, Upanishads, and Puranas. In these texts, the divine feminine is portrayed as the dynamic energy through which Brahman, the formless Absolute, manifests and sustains the universe.

Parallel currents are found in Judeo-Christian sources. The Hebrew idea of "Ruach" (Spirit) and "Shekinah" (Divine Presence) carry feminine grammatical gender and were understood by early mystics to denote the nurturing, indwelling, and redemptive energy of God. They are complemented by Gnostic writings and the Apocrypha, which frequently speak of the Holy Spirit as the Divine Mother—the Comforter, Teacher, and Source of wisdom who acts intimately in creation and redemption.

Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi and the Modern Paraclete

The central figure connecting historical tradition to the present is Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, regarded by followers as the living embodiment of the Adi Shakti and the Paraclete promised by Christ. Shri Mataji's teachings position her as the one who comes in modern times to guide humanity through the eschatological transition—the "Age of the Holy Breath" or the Aquarian Age—as forecasted by ancient and biblical prophecy.

Her revelation—that the Holy Spirit is in fact the Divine Feminine, the universal Mother within each human—is not merely doctrinal but experiential.Through the practice of Sahaja Yoga, individuals of every background are invited to awaken their Kundalini (the subtle manifestation of Adi Shakti within) and attain Self-realization—a direct, tangible experience of the Spirit evidenced by the Cool Breeze or vibrations felt on the body. This spiritual awakening transcends the boundaries of organized religions and opens a new chapter in human evolution, one that is inclusive, democratic, and collectively transformative.

Integration Across Traditions

The Adi Shakti sources position themselves at the nexus of religious pluralism, harmonizing concepts from Eastern and Western mysticism:

Hinduism

Adi Shakti is revered as the source from which Shiva and Vishnu derive power, the cosmic energy that gives rise to all incarnations and avatars.

Christianity & Judaism

She is recognized as the feminine face of God—the Holy Spirit or Shekinah—who delivers wisdom, inspiration, and unconditional love to prophets and believers.

Gnostic & Esoteric Traditions

The Divine Mother appears as Sophia, the eternal Wisdom, guiding the soul's descent and ascent through visible and invisible worlds.

Shri Mataji's teachings do not simply collate these strands; they actively reinterpret, clarify, and fulfill the eschatological promises found within them. She asserts that the expected "Age of the Comforter"—when the Holy Spirit would testify anew for Christ and bring about global redemption—is now at hand. This is not evidenced in sectarian belief but in the spontaneous, verifiable phenomenon of mass Self-realization and spiritual ascent through Sahaja Yoga.

Relevance to Contemporary Eschatology

The Adi Shakti tradition's sources are especially relevant to modern eschatological thought. Ancient expectations of a messianic age—whether in the form of the return of Christ, the arrival of the Mahdi in Islam, the coming of Kalki in the Hindu tradition, or the birth of a new Israel—are reframed as contiguous and mutually illuminating events, not as competitive or mutually exclusive prophecies. Shri Mataji's teachings point to a realization that the era in which spiritual transformation and divine testimony manifest most powerfully is now, and it is universally accessible.

The Aquarian Age, according to these sources, is characterized by unprecedented advances in spiritual consciousness, collective harmony, and new understandings of interconnectedness. Technologies and social changes are interpreted as outer signs of a much deeper inner renaissance—the ongoing birth of the kingdom of God within humanity, facilitated by the outpouring of the Divine Feminine and testified by direct spiritual experience.

Experiential Verification and Inclusive Practice

A distinctive hallmark of the Adi Shakti sources, as presented by Shri Mataji, is the insistence upon experiential verification. Unlike traditions that depend solely on faith, external ritual, or intellectual assent, Sahaja Yoga and the Adi Shakti path invite practitioners to test spiritual truths firsthand. The awakening of the Kundalini is marked not by subjective emotion but by objective physiological changes: cool or warm vibrations, relief of bodily and psychological disorders, and the establishment of thoughtless awareness (samadhi).

This insistence on lived experience underpins Shri Mataji's critique of religious formalism and dogma, urging seekers to move beyond inherited belief systems toward a universal gnosis. In this light, the Adi Shakti tradition fosters interreligious dialogue, mutual respect, and collective spiritual growth. People from all backgrounds are welcomed, and the process of Self-realization is proclaimed to be open to all, free of charge and organizational barriers.

Situating the Sources within Academic and Interreligious Discourse

From an academic perspective, Adi Shakti sources offer rich material for the study of comparative religion, mysticism, pneumatology, and gendered understandings of the divine. They challenge prevailing narratives in theology that have marginalized the feminine, proposing a well-documented alternative based in both scriptural exegesis and spiritual practice.

The sources engage in rigorous historical analysis, drawing on canonical and extra-canonical texts, linguistic studies (such as the feminine form of Ruach in Hebrew), and the historical evolution of mystical traditions across continents.

They also contribute meaningfully to ongoing discussions about the role of living revelation, the intersection of religion and science, and the democratization of divine grace.

The Global Impact and Continuing Evolution

Since their initial emergence, Adi Shakti sources—distributed through websites, academic papers, lectures, and Sahaja Yoga centers—have impacted millions worldwide. The flowering of Sahaja Yoga as an international movement parallels the growing academic and popular interest in feminine divinity, collective consciousness, and global eschatological themes.

Shri Mataji's message and the Adi Shakti tradition persist as a dynamic force, inviting seekers, scholars, and communities to participate in what may be the most consequential spiritual renaissance in recent history. The tradition's focus on inclusivity, experiential truth, and the harmonization of religious differences situates the Adi Shakti sources as indispensable references for anyone investigating the future of religion, spirituality, and human development.

Conclusion

In summary, the Adi Shakti sources offer a transformative lens through which to view the evolution of humankind, divine revelation, and universal harmony. By situating themselves at the convergence of Eastern and Western mystical traditions, they present not only a model of spiritual fulfillment but also a roadmap for the realization of prophecy, inner peace, and collective enlightenment in the modern world. Their significance lies in their ability to communicate ancient truths in a contemporary idiom, to foster authentic spiritual experiences, and to catalyze the ongoing rebirth of sacred consciousness across the globe.

Continue Your Awakening:

NATURE OF THE DIVINE MOTHER OR HOLY SPIRIT

The Goddess is Supreme Feminine Guru

Worshiping Devi is Direct Worship of Brahman

MahaDevi Research Paper (PDF)

The Divine Feminine in China

The Indian Religion of Goddess Shakti

The Divine Feminine in Biblical Wisdom Literature

Divine Feminine Unity in Taoism and Hinduism

Shekinah: The Image of the Divine Feminine

The Feminine Spirit: Recapturing the Heart of Scripture

Islam and the Divine Feminine

Tao: The Divine Feminine and the Universal Mother

The Tao as the Divine Mother: Embracing All Things

The Tao of Laozi and the Revelation of the Divine Feminine

Doorway of Mysterious Female ... Within Us All the While

The Eternal Tao and the Doorway of the Mysterious Female

Divine Feminine Remains the Esoteric Heartbeat of Islam

Holy Spirit of Christ Is a Feminine Spirit

Divine Feminine and Spirit: A Profound Analysis of Ruha

The Divine Feminine in Sufism

The Primordial Mother of Humanity: Tao Is Brahman

The Divine Feminine in Sahaja Yoga

Shekinah: She Who Dwells Within

Shekinah Theology and Christian Eschatology

Ricky Hoty, The Divine Mother

Centrality of the Divine Feminine in Sufism

A God Who Needed no Temple

Silence on (your) Self

The Literal Breath of Mother Earth

Prophecy of the 13 Grandmothers

Aurobindo: "If there is to be a future"

The Tao Te Ching and Lalita Sahasranama stand alone

New Millennium Religion Ushered by Divine Feminine

A Comprehensive Comparison of Religions and Gurus