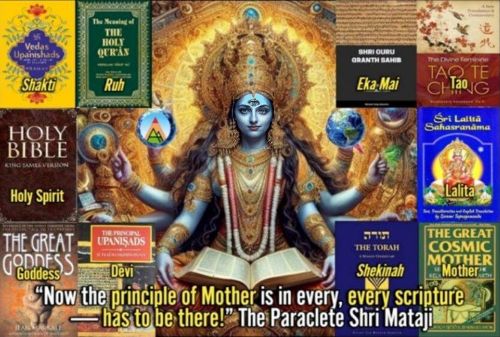

Shekinah: She Who Dwells Within All Beings

This page reveals the Shekinah—the indwelling feminine Presence of God in Jewish mysticism. Born from the root Sh-Kh-N, “to dwell,” Shekinah is the Spirit who abides among the people, especially in exile, suffering, and sacred ritual. She is the cloud of glory in the Mishkan, the Sabbath Bride, the compassionate face of YHVH. In Kabbalah, Shekinah is Malkhut—the gateway between divine transcendence and earthly experience. Her exile mirrors ours; her redemption is our awakening. Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi identified this same indwelling Spirit as Kundalini—the Divine Mother within. Shekinah and Kundalini are not separate truths, but one universal Feminine who dwells within, heals, and transforms. The Mother has always been here. She never left.

"God is always referred to as 'He' in the Masculine Gender. The feminine gender is not used because God is an active force in the universe."

THE POETIC IMAGE of YHVH giving birth satisfied a hunger I had not been consciously aware of. Still, could a Jewish God become a woman giving birth? Was it really possible to pray to a feminine YHVH? Could 'She' authentically be part of a religion that seemed to allow only the masculine metaphor?

Soon after my acknowledgment of the need to seek the feminine face of God, I was introduced to kabbalistic and hasidic texts by members of the New York and Boston Havurot (a religious community of peers).(p.20) Lo and behold! The 'Goddess' was alive and well in the midst of my own tradition.

As it is written in the twelfth-century mystical text known as the Zohar, 'Thou shalt have no other gods before Me. Said R. Isaac, 'This prohibition of other gods does not include the Shekinah'' (Zohar, 86a)

Shekinah, the feminine Presence of God, is a central metaphor of divinity in Jewish mystical and midrashic texts from the first millennium C.E. onward. I was amazed to discover this focus on the feminine divine when I began to read the texts myself. I felt like an orphan who uncovered documents that proved her mother was not dead. All the ambivalence about 'God She' was replaced with the fervor of an explorer who has just been given the right treasure map.

I plunged into the stacks of the Jewish Theological Seminary library and began hounding my teachers for information about my newly discovered relative. Who was She? Where did She live? Would She speak to me in a language I could understand?

What I found was both inspiring and disappointing. To begin with, everything written about the Shekinah appears to have been authored by men. Women's relationship to the Shekinah is nowhere recorded. Yet much of the material about the Shekinah seems to draw from that vast wellspring of the human unconscious that formulates images in archetypes even as it draws upon specific cultural influences.

The idea of Shekinah in Jewish tradition testifies to the basic human impulse to express the experience of the numinous through symbols that include the 'feminine'. Kabbalistic works that describe the Shekinah may incorporate aspects of women's experience in implicit ways. Without women's voices interpreting and composing Shekinah texts for themselves, however, we can never fully grasp women's experience of the divine.

The term Shekinah is an abstract noun of feminine gender derived from the Hebrew root Sh-Kh-N, meaning 'to dwell' or 'to abide.' The word Shekinah first appears in the Mishnah and Talmud (c.a. 200 C.E.), where it is used interchangeably with YHVH and Elohim as names of God.(p.21) Shekinah evolved from the word Mishkan, which refers to the tent the Israelites constructed in the wilderness to house the altar, the seven-branched menorah, the stone tablets, and the twelve loaves of bread baked as an offering to God. After the Israelites received the Torah, they were instructed to build the Mishkan, 'So I can dwell among you.' When the shrine was completed, YHVH appeared to the people as a cloud of light indicating His Presence.

The destruction of the first Temple in Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. by the Babylonians resulted in the first exile of the Jewish people and engendered a crisis of faith. The Israelites wondered whether God's Presence, which had previously dwelled in the Temple, would continue to abide in their exile. Ultimately that concern was answered in the affirmative. God's abiding Presence, formerly represented as a cloud of glory, became known as the Shekinah. The Shekinah was said to accompany the people into exile and would appear to them whenever the people occupied themselves with the study of Torah or performed good deeds. Although the Temple was destroyed, ritual and the behavior of the people became the new dwelling place for God's Presence.

Over time, the biblical themes of exile and redemption and the historical experience of the Jewish people under Roman and Christian Europe continued to shape the meaning of Shekinah. Women's role as professional mourners and the midrashic image of Israel as God's marriage partner were particularly influential in the evolution of Shekinah into a feminine aspect of God. By 1000 C.E., the very mythologies so suppressed in the Bible erupted in the heart of Jewish mysticism, known as the kabbalah, and Shekinah became YHVH's wife, lover, and daughter.

Kabbalists conceive of God in Neoplatonic terms, as a dynamic complex of ten energies or spheres that emanate from a hidden and unknowable Source. The whole system is known as the Tree of Life. The divine spheres represent the hidden and inner life of God, which becomes manifest in the material world of existence through the medium of the Shekinah. However, the Shekinah occupies the bottom rung of the hierarchical chain of divine emanations.

HarperCollins Publishers, 10 East 53rd Street, New York, 1995

The Divine Feminine: Comparing Shekinah and Kundalini in the Context of Global Spiritual Traditions

Introduction

The concept of the Divine Feminine has existed across cultures and religious traditions throughout human history, though it has often been marginalized or suppressed within patriarchal religious structures. In recent decades, there has been a growing interest in recovering and reintegrating feminine aspects of divinity within various spiritual traditions. This analysis examines two significant expressions of the Divine Feminine from different religious contexts: the Shekinah in Judaism and the Kundalini in Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi's teachings.

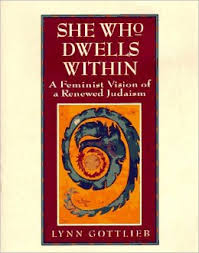

Lynn Gottlieb's "She Who Dwells Within: A Feminist Vision of a Renewed Judaism" explores the concept of Shekinah, the feminine presence of God in Jewish tradition, particularly as developed in mystical and Kabbalistic texts. Gottlieb, one of the first women to become a rabbi in Jewish history, approaches this topic from both scholarly and feminist perspectives, seeking to recover and reinterpret the feminine divine within Judaism.

Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi (1923-2011), founder of Sahaja Yoga, taught extensively about Kundalini, describing it as the motherly energy within each individual that, when awakened, connects the person to the divine. She explicitly connected this concept to the Holy Ghost in Christian terminology, suggesting a universal feminine divine principle that transcends specific religious boundaries.

Despite emerging from different religious traditions and historical contexts, these two concepts share remarkable similarities in how they conceptualize and experience the divine feminine. Both represent feminine divine energy that dwells within, serves as a mediator between the transcendent divine and material existence, and catalyzes transformation and spiritual awakening.

This analysis will examine these concepts in depth, compare their similarities and differences, and place them within the broader context of divine feminine expressions across world religions. By exploring these connections, we can gain insight into what appears to be a universal human recognition of feminine aspects of divinity, even in traditions that have historically emphasized masculine divine imagery.

The parallels between these concepts, along with similar divine feminine expressions in other traditions, suggest that humanity may indeed be slowly awakening to the Mother, the Shekinah or Kundalini who resides in all beings and awakens them to their eternal, divine nature. This analysis seeks to illuminate this awakening by exploring these rich spiritual traditions and their contemporary significance.

Shekinah: The Divine Feminine in Judaism

Etymology and Historical Development

The term Shekinah derives from the Hebrew root Sh-Kh-N (שכן), meaning "to dwell" or "to abide." This etymology is profoundly significant as it directly connects to the concept's primary function: representing God's dwelling presence among the people. As Lynn Gottlieb explains in "She Who Dwells Within":

The term Shekinah is an abstract noun of feminine gender derived from the Hebrew root Sh-Kh-N, meaning 'to dwell' or 'to abide.' The word Shekinah first appears in the Mishnah and Talmud (c.a. 200 C.E.), where it is used interchangeably with YHVH and Elohim as names of God.

The concept evolved from the word Mishkan, which referred to the physical tent or tabernacle that housed sacred objects during the Israelites' wilderness journey.

According to biblical tradition, after receiving the Torah, the Israelites were instructed to build the Mishkan "so I can dwell among you." When completed, YHVH appeared to the people as a cloud of light indicating Divine Presence.

The destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem in 586 BCE by the Babylonians created a theological crisis for the Jewish people. They wondered whether God's Presence, which had previously dwelled in the Temple, would continue to abide with them in exile. The concept of Shekinah emerged prominently during this period as a response to this crisis, representing the divine presence that could accompany the people regardless of physical location or temple structure.

The Shekinah was said to accompany the people into exile and would appear to them whenever the people occupied themselves with the study of Torah or performed good deeds. Although the Temple was destroyed, ritual and the behavior of the people became the new dwelling place for God's Presence.

Over time, the biblical themes of exile and redemption and the historical experience of the Jewish people under Roman and Christian Europe continued to shape the meaning of Shekinah. Women's role as professional mourners and the midrashic image of Israel as God's marriage partner were particularly influential in the evolution of Shekinah into a feminine aspect of God.

By 1000 CE, the concept underwent a significant transformation within Jewish mysticism (Kabbalah):

By 1000 C.E., the very mythologies so suppressed in the Bible erupted in the heart of Jewish mysticism, known as the kabbalah, and Shekinah became YHVH's wife, lover, and daughter.

This evolution represents a remarkable development within a monotheistic tradition that had generally avoided gendered language for God outside of masculine metaphors. The emergence of explicitly feminine divine imagery within Kabbalah suggests a persistent human need to express the divine through both masculine and feminine symbolism, even within traditions that officially emphasize divine transcendence beyond gender.

Theological Significance

The Shekinah concept holds profound theological significance within Jewish tradition. It addresses the fundamental theological question of how the transcendent, infinite God can be present and accessible to finite human beings. The Shekinah represents God's immanent presence, the aspect of divinity that can be experienced directly in the world.

In rabbinic literature, the Shekinah is associated with God's compassionate presence among the people, particularly in times of suffering. There are numerous midrashic accounts of the Shekinah accompanying Israel into exile, sharing in their suffering, and awaiting redemption alongside them. This portrayal of divine compassion and solidarity creates a powerful theological image of a God who does not remain distant from human suffering but enters into it.

The Zohar, a foundational Kabbalistic text, distinguishes Shekinah from "other gods," placing her in a unique category within Jewish monotheism:

As it is written in the twelfth-century mystical text known as the Zohar, 'Thou shalt have no other gods before Me. Said R. Isaac, 'This prohibition of other gods does not include the Shekinah.'

This suggests a recognition of the divine feminine as an integral aspect of God rather than a separate deity, maintaining monotheism while expanding the imagery used to conceptualize the divine.

The Shekinah also plays a crucial role in Jewish prayer and ritual practice. In traditional Jewish thought, when ten Jews gather for prayer (a minyan), the Shekinah is said to dwell among them. Similarly, the Sabbath is sometimes personified as the Shekinah or as a bride, with Friday evening prayers welcoming her presence. These ritual associations emphasize the experiential dimension of the Shekinah concept—it is not merely a theological abstraction but a presence that can be encountered through communal religious practice.

Kabbalistic Understanding

In Kabbalistic thought, the Shekinah takes on additional layers of meaning within the complex symbolic system of the sefirot (divine attributes or emanations). As Gottlieb explains:

Kabbalists conceive of God in Neoplatonic terms, as a dynamic complex of ten energies or spheres that emanate from a hidden and unknowable Source. The whole system is known as the Tree of Life. The divine spheres represent the hidden and inner life of God, which becomes manifest in the material world of existence through the medium of the Shekinah.

Within this system, the Shekinah is identified with Malkhut (Kingdom), the tenth and lowest sefirah, representing the divine presence in the material world. As the lowest emanation, the Shekinah serves as the interface between the divine and material realms, the point at which transcendent divinity becomes immanent and accessible to human experience.

The Kabbalistic understanding of Shekinah also incorporates a cosmic drama of exile and redemption. According to this mythology, the Shekinah became separated from the higher sefirot (particularly from Tiferet, representing the masculine aspect of God) due to human sin. This separation is understood as the source of disharmony and suffering in the world. Through righteous action and mystical practice, humans can participate in the reunification of the Shekinah with the higher aspects of God, contributing to the healing and redemption of both the divine and the world.

This mythological framework provided Kabbalists with a powerful way to understand their own experiences of exile and suffering, as well as their spiritual practices. By connecting human action to cosmic processes, it gave profound significance to religious observance and ethical behavior, which were seen as contributing to the restoration of divine harmony.

Feminist Perspectives

Lynn Gottlieb's exploration of the Shekinah is explicitly informed by feminist concerns and perspectives. She notes the limitations of traditional sources while also recognizing their value:

What I found was both inspiring and disappointing. To begin with, everything written about the Shekinah appears to have been authored by men. Women's relationship to the Shekinah is nowhere recorded. Yet much of the material about the Shekinah seems to draw from that vast wellspring of the human unconscious that formulates images in archetypes even as it draws upon specific cultural influences.

This observation highlights a central tension in feminist approaches to traditional religious concepts: how to recover and reinterpret valuable spiritual resources while acknowledging their emergence within patriarchal contexts. Gottlieb suggests that despite being articulated by men, the Shekinah concept may incorporate aspects of women's experience "in implicit ways" and draws from archetypal patterns that transcend specific cultural limitations.

For Gottlieb and other Jewish feminists, the Shekinah provides a foundation for developing more gender-inclusive Jewish theology and practice. By recovering and emphasizing this feminine divine image from within Jewish tradition, they challenge the assumption that God can only be conceptualized in masculine terms without abandoning traditional sources.

Gottlieb's personal response to discovering the Shekinah tradition illustrates its emotional and spiritual significance for contemporary Jewish women:

I was amazed to discover this focus on the feminine divine when I began to read the texts myself. I felt like an orphan who uncovered documents that proved her mother was not dead. All the ambivalence about 'God She' was replaced with the fervor of an explorer who has just been given the right treasure map.

This powerful metaphor of discovering that one's "mother was not dead" speaks to the sense of loss and recovery that many women experience when encountering feminine divine imagery within traditions that have predominantly emphasized masculine language for God.

Contemporary feminist approaches to the Shekinah often expand beyond traditional Kabbalistic interpretations, incorporating insights from psychology, ecology, and other spiritual traditions. Some emphasize the Shekinah's association with the earth and embodiment, connecting her to ecological concerns. Others focus on her role in validating women's spiritual leadership and religious experience. These diverse approaches demonstrate the continuing vitality and adaptability of the Shekinah concept in addressing contemporary spiritual needs.

The recovery of the Shekinah within feminist Jewish spirituality represents part of a broader movement across religious traditions to reclaim and reintegrate feminine divine imagery. This movement responds to the recognition that exclusively masculine God-language has contributed to the devaluation of women and the feminine in religious communities and the wider culture. By recovering the Shekinah and similar concepts, feminist theologians and practitioners seek to create more balanced and inclusive spiritual frameworks that honor both feminine and masculine aspects of divinity and humanity.

Kundalini: The Divine Mother Within

Origin and Concept

The concept of Kundalini originates in ancient Indian spiritual traditions, particularly within Tantra and various schools of Yoga. The term "Kundalini" comes from the Sanskrit word "kundala," meaning "coiled," suggesting the serpent-like energy that rests at the base of the spine. In Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi's teachings, Kundalini is understood as:

The primordial Mother who is the Holy Ghost and She is reflected within us as the Kundalini. In our heart is reflected the God Almighty. It is He who is the witness of whatever we are doing. This power manifests everything within us and then resides in a sleeping state in that triangular bone and is said to be residual because it has not yet manifested itself.

Shri Mataji's interpretation synthesizes traditional Kundalini concepts with Christian terminology, presenting it as a universal spiritual principle that transcends any single religious tradition. She emphasizes that the awakening of Kundalini represents the fulfillment of spiritual promises across religions:

This is the power of our desire which is true and the only desire we have which is pure. Because all other desires are not true. If they were true, any one of them when satisfied, we would not have desired for anything else.

This understanding positions Kundalini as the fundamental spiritual longing within each individual, the desire for union with the divine that underlies all other transient desires.

Location and Awakening Process

In Shri Mataji's teachings, the Kundalini has a specific physical location within the human body:

This power... resides in a sleeping state in that triangular bone called as sacrum. Just see, Greeks knew about it, that's why they called this bone as sacrum. But what is this bone in the biblical understanding—it is the reflection of the Holy Ghost.

The awakening process is described as a spontaneous rising of this energy through the central channel (sushumna nadi) of the subtle body, piercing through various energy centers (chakras) until it reaches the crown of the head (sahasrara chakra), resulting in self-realization or spiritual enlightenment.

Shri Mataji emphasizes that this awakening is not achieved through strenuous effort but is a natural process that occurs through divine grace:

It is a living process of our evolution and if it is done by the power of a living God, then it has to be very simple, has to be very easy—like if you have to sprout a seed you just put it in the Mother Earth, and the seed has a capacity to become the plant and the Mother Earth has a capacity to sprout it. In the same way, this happening has to take place.

Relationship to the Holy Ghost

One of Shri Mataji's distinctive contributions is her explicit identification of Kundalini with the Holy Ghost in Christian theology:

We have to understand that if there is a Father God and a Son—there has to be a Mother. So this is the primordial Mother who is the Holy Ghost and She is reflected within us as the Kundalini.

This trinitarian interpretation presents Kundalini as completing the divine family—Father, Son, and Mother (Holy Ghost)—and thus offers a feminine dimension to Christian theology while maintaining its essential structure. She connects this understanding to biblical concepts of rebirth:

This is what Christ has exactly said when he said you are to be born again. He didn't say that you just ask somebody to do an exercise of putting some water on top of your head and then say now you are baptised. No. There is a true baptism of the real awakening of this Kundalini passing through these six centres above, piercing through your fontanel bone area and giving you the true experience of the breeze of the Holy Ghost coming out of your own head and this cannot be by just putting water by somebody. It has to happen within yourself and you have to seek the truth, and not something that just satisfies you for the time being.

Transformative and Healing Power

The awakened Kundalini is described as having profound transformative and healing effects:

When this Kundalini rises She passes through these centres on the physical level and you get physical health. Some people say, 'Mother, you heal us or cure us'—is not true. It is your own Kundalini. it's your own Mother within you.

This emphasizes that the healing power comes from within the individual rather than from an external source. The process is described as automatic and guided by the Kundalini itself:

Everybody has an individual Mother. When She rises, She actually fulfils the need of every subtle centre that supplies to your gross centres, because these are the abstract or we can say are the subtle centres which are first fulfilled and they look after your plexuses, that's how you get healed automatically.

The transformation extends beyond physical healing to encompass spiritual awakening and the development of higher consciousness:

Once the desire of becoming one with the Divine manifests then you don't want anything—you want to give. Like you want to be the light and then you become the light that emits light and emancipates others—raises them to the level of their Spirit by giving them peace and bliss.

Comparative Analysis: Shekinah and Kundalini

| Dimension | Shekinah | Kundalini |

|---|---|---|

| Etymology | From Hebrew "Sh-Kh-N" (to dwell) | From Sanskrit "kundala" (coiled) |

| Primary Representation | Feminine presence of God dwelling among people | Primordial Mother energy coiled at base of spine |

| Function | Mediates between transcendent God and material world | Mediates between individual and divine consciousness |

| Transformative Power | Brings divine presence into exile; facilitates redemption | Awakens spiritual potential; leads to self-realization |

| Light Symbolism | Manifests as cloud of glory; associated with menorah | Described as rising energy; associated with enlightenment |

| Focus | Primarily communal (dwells among people) | Primarily individual (resides within each person) |

| Historical Development | Evolved from Temple presence to mystical concept | Evolved from esoteric practice to universal principle |

| Physical Location | No specific bodily location (dwells among/in community) | Located at base of spine (sacrum bone) |

Universal Implications

The striking parallels between Shekinah and Kundalini, despite their origins in different religious traditions, suggest a universal recognition of the Divine Feminine as immanent, transformative power. Both concepts:

- Represent the divine as accessible and present within creation

- Embody feminine qualities of nurturing, compassion, and creative power

- Serve as mediators between transcendent divinity and material existence

- Are associated with light and transformative energy

- Address fundamental human experiences of exile/separation and the longing for return/union

The Divine Feminine Across Religious Traditions

Hinduism: Shakti - The Power of the Feminine

In Hinduism, Shakti represents the active, dynamic principle of the divine, often personified as the Goddess in various forms (Durga, Kali, Lakshmi, etc.). Like Shekinah and Kundalini, Shakti is understood as the creative power that brings the universe into manifestation and sustains it.

Christianity: Sophia and the Holy Spirit

While mainstream Christianity has emphasized masculine imagery for God, feminine divine concepts have persisted in the figure of Sophia (Divine Wisdom) and in some interpretations of the Holy Spirit as feminine (based on the Hebrew word ruach being feminine).

Islam: The Feminine Attributes of Allah

Though Islam strongly emphasizes divine transcendence beyond gender, the 99 Names of Allah include many that express traditionally feminine qualities (The Compassionate, The Merciful, The Nurturer). Some Sufi traditions have developed more explicit feminine divine imagery.

Buddhism: Female Buddhas and Wisdom Deities

In Vajrayana Buddhism, female Buddhas and wisdom deities (like Tara and Prajnaparamita) represent enlightened feminine principles, often associated with wisdom and compassion.

Humanity's Awakening to the Divine Feminine

Historical Suppression and Reemergence

The marginalization of feminine divine imagery in many religious traditions reflects broader patterns of patriarchal social organization. However, as evidenced by the persistence of concepts like Shekinah and Kundalini, the Divine Feminine has never been completely erased.

Contemporary Significance

Today, there is growing recognition that recovering feminine divine imagery is essential for:

- Creating more balanced spiritual paradigms

- Validating women's spiritual authority

- Developing ecological consciousness

- Healing psychological and cultural imbalances

The future of spirituality may lie in recognizing the complementarity of feminine and masculine divine principles, as exemplified by:

Conclusion

The comparative study of Shekinah and Kundalini reveals profound similarities in how different religious traditions have conceptualized the Divine Feminine as immanent, transformative power. Despite historical suppression, these concepts have persisted and are now being recovered with new significance for contemporary spiritual seekers.

As Shri Mataji declared and Lynn Gottlieb's work confirms, the Divine Mother dwells within all beings, offering a direct path to spiritual awakening and wholeness. The growing recognition of this truth across religious boundaries suggests that humanity is indeed awakening to the eternal presence of the Divine Feminine within and among us.

References

1. Gottlieb, Lynn. She Who Dwells Within: A Feminist Vision of a Renewed Judaism. HarperCollins, 1995.

2. Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi. Public talk, Cardiff, UK. April 8, 1984.

3. Additional scholarly sources on comparative religion and feminine divine concepts.

Pariah Kutta (https://adishakti.org)

https://chat.deepseek.com/a/chat/s/c8af40ff-07c1-42dd-9705-63af46581651

Related Articles:

NATURE OF THE DIVINE MOTHER OR HOLY SPIRIT

The Goddess is Supreme Feminine Guru

Worshiping Devi is Direct Worship of Brahman

MahaDevi Research Paper (PDF)

The Divine Feminine in China

The Indian Religion of Goddess Shakti

The Divine Feminine in Biblical Wisdom Literature

Divine Feminine Unity in Taoism and Hinduism

Shekinah: The Image of the Divine Feminine

The Feminine Spirit: Recapturing the Heart of Scripture

Islam and the Divine Feminine

Tao: The Divine Feminine and the Universal Mother

The Tao as the Divine Mother: Embracing All Things

The Tao of Laozi and the Revelation of the Divine Feminine

Doorway of Mysterious Female ... Within Us All the While

The Eternal Tao and the Doorway of the Mysterious Female

Divine Feminine Remains the Esoteric Heartbeat of Islam

Holy Spirit of Christ Is a Feminine Spirit

Divine Feminine and Spirit: A Profound Analysis of Ruha

The Divine Feminine in Sufism

The Primordial Mother of Humanity: Tao Is Brahman

The Divine Feminine in Sahaja Yoga

Shekinah: She Who Dwells Within

Shekinah Theology and Christian Eschatology

Ricky Hoty, The Divine Mother

Centrality of the Divine Feminine in Sufism

A God Who Needed no Temple

Silence on (your) Self

The Literal Breath of Mother Earth

Prophecy of the 13 Grandmothers

Aurobindo: "If there is to be a future"

The Tao Te Ching and Lalita Sahasranama stand alone

New Millennium Religion Ushered by Divine Feminine

He is devoted utterly to the God who is the SelfZimmer

A Comprehensive Comparison of Religions and Gurus